Freshwater microorganisms documented in new book for all to explore

RENSSELAERVILLE — Linda VanAller Hernick has always been interested in water. She has been especially fascinated by what lives in its smallest drops.

After retiring from her work at the New York State Museum in 2014, Hernick was able to do more with her preferred pastime, collecting water samples and studying and photographing microscopic organisms. In 2015, she decided to compile her observations into a book, titled “Most Wonderful in the Smallest,” published this summer.

Hernick, 65, lives in Rensselaerville with her husband. She travels to various bodies of water surrounding her home to collect organisms: two swamps, a couple of ponds, even ditches on the side of the road.

Shooting

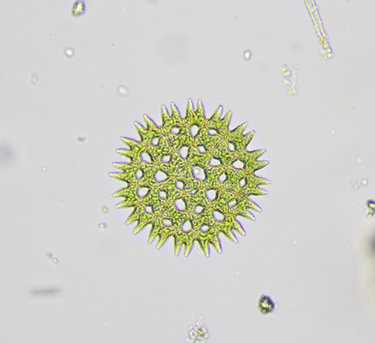

Hernick then observes the water samples under a microscope; algae, with its intricate structure, is especially beautiful, she says.

“You look at them and this is a single cell, and it’s pretty complex, even if it’s a single cell,” said Hernick. She also observes also tiny animals like copepods, but prefers focusing on single-celled creatures such as protists.

One other organism Hernick finds interesting are amoebae, possibly best known as single-celled blobs, which can be found with shells they either secrete or make from collecting particles of quartz, iron, or manganese.

“You see a picture of an amoeba in a textbook, it just looks like this blob with pseudopodia sticking out … ,” she said. “There’s this whole other group of amoeba with little tiny shells that they create.”

She takes photos of these creatures as well, but sometimes struggles to take a clear shot since they move around. Many who do this will kill, stain, and mount a microorganism for a picture, she says, but she herself will not do this.

“I can’t bring myself to kill these things,” said Hernick. “They’re just too beautiful.”

Hernick uses specific tools: a water sampling device consisting of a plastic flask attached to a long arm to collect the water that she then stores in an aquarium, pipets and slides to observe samples under a microscope, and a special microscope that allows a single-lens reflex camera to be attached to take pictures.

But she wants readers to know that they can practice microscopy as well, and with much less intricate equipment. Used microscopes may be found online, and point-and-shoot cameras can take shots from the viewfinder, for example.

“Most Wonderful in the Smallest,” is the title of a new book by Linda VanAller Hernick on microscopic organisms. The title is derived from an 1869 watercolor painting by H.C. Richter of the same name, seen here on the cover.

Writing

Hernick kept a journal on her observations, and decided to write her book in this format.

“It just seemed to me to be more interesting that way,” she said. “The reader can kind of go out with me to the site where I collect and I describe where it is, what it looks like, what the day is like.”

Microorganisms can exist even in cold temperatures, notes Hernick. Some move deeper into the water, others clump up together, and some disappear for the winter only to return in the warmer half of the year. Hernick collects samples year-round.

In her book, she describes how she once was stopped by a town highway worker while she was attempting to break the ice in a ditch along the side of the road.

“He asked me if I was OK,” said Hernick. “I think he thought something happened to me.”

The making of a scientist

Hernick grew up in the Schoharie Valley in Middleburgh.

“I think I’ve always been interested in natural history in general,” she said.

When she was 10 years old, Hernick was given the book “Pioneer Germ Fighters” by Navin Sullivan. The book included stories of the first biologists who studied microscopic pathogens. It’s cover included a line drawing of Alexander Fleming — the Scottish biologist who discovered penicillin — poring over a microscope.

“I was fascinated by that drawing,” said Hernick.

She asked for a microscope for Christmas, and received one that, although it was a toy, allowed her to pursue her interest in the microscopic world. Hernick graduated from the small, rural Middleburgh Central School District and attended The College of Saint Rose in Albany, where she received her bachelor’s degree in biology. She then attended the Albany School of Cytotechnology (now part of the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences) for a year before working for commercial cytopathology laboratories as a cytotechnician, where she screened for cancer and precancerous cells.

“Most of our work was actually pap smears,” she said, referring to the Papanicolaou smear that screens women for cervical cancer. Some of the greatest pressures of this job, said Hernick, was knowing that a mistake could be a life-or-death consequence for a person.

Hernick worked as a cytotechnologist full-time from 1975 to 1986.

“It was really interesting and I was happy to be helping people by trying to pick up cancers and things,” she said. “But there wasn’t any place for it to go.”

She quit her job in 1986, although she continued to work part-time as a cytotechnologist for another 5 years, and went on a road trip with her husband across the country, visiting paleontology sites.

Finding fossils

“I’d always been interested in paleontology anyway,” said Hernick. “But this kind of stirred things up.”

She then started taking graduate courses and in 1989, while visiting the New York State Museum for a geology course, told a state paleontologist there that she was available and willing to work as a technician. Six months later, the paleontologist called her and offered her a job.

She was hired to search for microscopic fossils, breaking down stones in acid and looking under a microscope for the teeth left behind by worms in order to determine the boundary between the Cambrian and Precambrian period.

“The time periods are based on fossils,” she explained.

This took several years. Hernick eventually began studying paleobotany.

“New York State, especially the Catskill Mountains, are full of plant fossils from the Devonian period,” she said.

In Gilboa, in Schoharie County, Hernick and a coworker discovered a fossilized tree, something that had never been found before, and worked with Cardiff University in Wales and the State University of New York at Binghamton to find out what kind of trees actually grew long ago in that area.

The lure of microorganisms

During her lunch breaks at the museum, Hernick would visit the State Library, where she came across a publication by the Quekett Microscopical Club, based in the United Kingdom. This edition included a watercolor illustration of microorganisms titled “Most Wonderful in the Smallest.” Hernick contacted the club’s curator about this drawing, who then invited her to join.

In Britain, there are many different clubs and societies like this, she said, while in the United States there are very few, as well as an overall lack of interest in microorganisms.

“When I first started out looking at these things, there isn’t much out there for the amateur … ,” she said. “I’d see a beautiful thing and say, ‘What is this?’ I had no way to find out in the beginning.”

This led Hernick to try to bring this knowledge to untrained people.

The scientific world itself is lacking when it comes to studies of microorganisms, said Hernick. Biodiversity studies tend to focus on macro-species. Grants are often given for molecular biology, such as the study of DNA.

“It’s intricate, it’s beautiful, it’s essential,” she said, explaining that these microscopic creatures are an important part of their ecosystem. Two-thirds of living things on Earth are microscopic, she said, and yet there is very little research or study of them.

“They may be tiny, but they’re important too; they’re part of the whole ecosystem,” she said.

Efforts to study microorganisms could lead to a better understanding of the importance wetlands, as well how forces such as climate change affect the whole of an ecosystem. A better understanding could also stop misconceptions; a common one is that all are a type of disease.

“It’s really gratifying … ,” said Hernick, of her book being published. “I just hope that there’s somebody out there that finds it as interesting as I have.”

She said she would like to continue studying these organisms, including going to new sites such as the ocean, and learning new photographic techniques.

“In a way, I’ve just scratched the surface,” she said.