One survivor's story: A decade of suffering follows domestic abuse

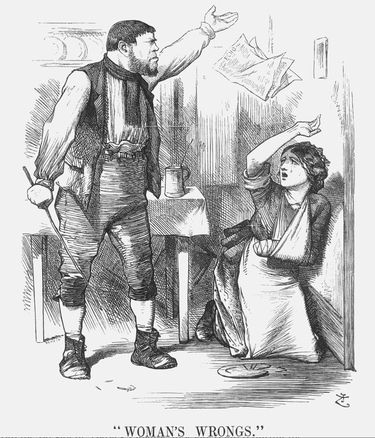

Domestic violence and society's unwillingness to deal with it are nothing new. Joseph Swain's 1874 cartoon in London's "Punch" magazine shows a husband preparing to beat his battered wife. He tells her the authorities don't care as he flings the newspaper at her in which the comments printed in the cartoon's caption are reported: The matter of violence toward married women has been raised in the House of Commons but Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli used the occasion to gain laughs, while allowing the matter to be shelved again.

GUILDERLAND — One in three women over the age of 18 in the United States report experiencing rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner.

Domestic violence, according to Kim Anderson, a licensed social worker and associate professor at the University of Missouri, is a “serious global health issue.”

Anderson has dedicated 25 years of research to looking at how victims of domestic violence work to recover in the years following the end of the abusive relationship.

There is no limit, said Anderson, to the amount of time it may take to recover from abuse, and it is never too late to begin the process.

For one Guilderland woman, it has been nearly eight years since her divorce, and the abuse she suffered throughout her marriage still haunts her and affects every aspect of her life.

The abuse started shortly after their marriage began, she said, and was both emotional and physical.

Before they got married and moved in together, said the woman, her husband told her to get rid of all of her furniture and belongings, because he would buy her new things.

Once she moved in with him, though, he refused to get her furniture, and forced her to sleep on an old crib mattress on the floor. He had a large dresser that he used for himself, but would not allow her to keep her clothing in it. She kept her clothes in plastic bags.

“He treated me like I just didn’t matter,” she said. “I was not allowed to do anything without permission, even use the bathroom — he would block the door while I stood there and begged.”

Her ex-husband could not be reached for comment.

Anderson said deprivation is one of the hallmarks of abuse.

The woman said she was not allowed to spend money on anything for herself, and her husband destroyed household items when he was angry, kicked her cat, and threatened her son from a previous marriage.

She was not allowed to have friends and her husband had to know where she was and what she was doing at all times.

Things escalated in 2005 when, one day, her husband became angry that her son’s books were scattered across a table, and took them and threw them out the window, into the rain and mud.

Her son, who was on a full ROTC scholarship at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, ran outside to gather the books, and her husband followed him and began to beat him. He hit him over the head with a shovel, twice.

“I saw everything,” she said. “The second time he was hit, he fell to his knees, and his eyes rolled back in his head. He was trying to say ‘mom’ but he couldn’t speak.”

She said her son crawled into the house and she called 9-1-1; when her husband came in and asked who she was talking to, he told her she was “dead meat.”

Her husband began wrapping toilet paper around her son’s head in an attempt to stop the bleeding, she said.

Her son was taken to the hospital by ambulance, where, she said, they told him he had a small laceration on his head that they would staple back together.

The next day, he couldn’t speak correctly, his head was swollen, and he couldn’t see out of one eye.

She took him to a different hospital, where a computed tomography scan of his head showed bone fragments floating in his brain fluid.

As a result of his injuries, he has seizures, vision problems, and struggles with impulse control. He also suffers from posttraumatic stress disorder. He had to give up his scholarship at RPI and attend college elsewhere; he couldn’t be commissioned as an officer in the military — his long-held goal.

“I never in my wildest dreams imagined that the man I fell in love with could be so aggressive toward my son,” said the woman. “I remember making excuses, saying, ‘Yeah, he says these things to me, he hurts me, but he’d never hurt my child.’”

A police report filed after the incident, with the Guilderland Police Department, says that her husband was arrested for assault with intent to cause physical injury, a felony.

It said that when police arrived, her son was bleeding from his head and her husband was bleeding below his left eye.

Her husband reported to the police that his stepson had punched him in the face and that, in response, he swung the shovel and hit him in the back of the head.

Her husband said he then brought his stepson into the house and tried to bandage his head for him, but, when he realized the severity of his injury, he had his wife call emergency services.

An order of protection was issued against her husband, who legally was not supposed to come in contact with her son, and therefore should have stayed away from the house where she and her son were living.

He came to the house the day after he was released from jail, she said, and started taking money and his belongings.

“I told him he wasn’t supposed to be there, but he kept telling me I ‘wasn’t going to get away with this,’” she said.

After he left, she said, she contacted the police department to let the police know he had violated his order, and an investigator asked if he had hurt her. When she said no, the department neglected to follow up, she said.

Anderson said the least used strategy of women who had suffered domestic violence and recovered was legal intervention.

“Police involvement and protection orders were not necessarily helpful, because of the difficulty with enforcement,” said Anderson.

Only 38 percent of the women she studied filed charges against their abusers, and only 35 percent sought legal aid.

After the Guilderland woman’s husband had violated the order of protection without consequence, he would come to the house nearly every night, parking away from the house and entering through the garage.

“He would tell me that I couldn’t call anybody, because if I did, ‘I knew what would happen,’” she said.

He told her to “keep her mouth shut” while he got things “straightened out.”

She said she had no family she could go to and she had her husband’s family telling her to “make it all go away” and that she was “ruining the family’s name.”

Eventually, she said, her husband managed to get his stay-away order of protection changed to a refrain-from order of protection, meaning he could be in the same household as her son as long as he did not harass or threaten him.

He was in a domestic violence accountability class, ordered by the court, and she had to give a victim impact statement.

“My statement said things like we wanted to forgive him and we wanted to move on,” she said. “I was saying what I thought I should to protect myself from him.”

Anderson said that nearly all of the women in her study reported placating their abusers.

The abuse to the Guilderland woman continued once he moved back into the house, she said, but even worse, as if he wanted to punish her for what had happened to her son.

When she and her husband would fight, her son would cower in his bedroom, she said.

In 2007, they got in an argument, and her husband broke apart the kitchen, throwing the oven out onto the lawn.

After he left, she called the police, and was told that her husband was there at the department, claiming that she had assaulted him.

He was arrested at that time, but she told the officer that she did not want to issue an order of protection against him.

“I said, ‘I can’t, because he will kill me,’” she said.

She said she was in contact with a victims’ advocate and requested that the advocate meet her outside of the house, because her husband told her he had set up recorders inside the house. The advocate, she said, told her it would be inappropriate to meet outside her home, and would only call her during the day, when her husband was home and she couldn’t talk.

“There was no help,” she said. “I had no one.”

Her husband’s probation officer once asked her why she didn’t just leave.

“My son was over 21 and couldn’t be with me in a shelter,” she said. “I didn’t want to be separated from him and he would have nowhere to go.”

In May of 2007, her husband filed for divorce.

“He had moved out by then because he met somebody else,” she said.

She did not want a divorce because she wanted to keep her social security and medical insurance, so she tried to prove he didn’t have grounds for divorce.

The divorce was granted, and the court awarded her temporary support, which, she said, will end this year.

“It didn’t make me feel safe, though,” she said. “As long as I was getting money from him I was a thorn in his side.”

Even though it has been nearly eight years, she doesn’t feel as though she has recovered.

She is unable to find work, due to a disability, and does not have the money to make necessary repairs to her house; she still does not have a functioning kitchen, since hers was destroyed in 2007.

She also does not have a support system.

“There are some cases where your family doesn’t support you, and others where they are just ashamed of you,” she said.

A study performed by Anderson showed that victims of domestic violence recovered differently based on the length of the relationship, level of education, access to formal resources, and informal support systems.

“Something really essential for these women after they left these relationships was informal support systems, such as friends and family,” said Anderson. “That is probably the number-one factor in recovery, especially in the first two years.”

Second, she said, were formal resources, including therapy and domestic violence services.

Sixty percent of the women she studied, who had recovered, had talked to or worked with someone at a domestic violence shelter or hotline.

The less formal education a woman had, the harder recovery was, said Anderson.

Those who did not have access to educational resources had a harder time finding work to generate income and had fewer options available for securing safe housing.

Overall, Anderson was able to break recovery down into three stages — self-care, self-transformation, and self-transcendence.

“These are progressive, but not mutually exclusive,” she said.

The first stage, self-care, involves disclosing the abuse — to friends or family — and establishing a new sense of safety and control. It also involves establishing a new sense of self, inclusive of newfound strengths.

The second stage, self-transformation, includes realizing the capacity for potential and directing energy toward new life goals. This could be finding a new job, going back to school, or even volunteering.

The third and final stage, self-transcendence, involves establishing a renewed purpose and meaning in life, including the belief that her struggles have made her a better person. It often involves using her own experiences to help others.

“One of the things that has interested me the most in working with these women is that some people view them as damaged or dysfunctional, but I see them as people with amazing strength and the power to persevere,” said Anderson.

The potential for recovery is always there, she said, no matter how long ago the relationship ended.

“People are always in the process,” said Anderson. “The potential is always there, and reaching out and finding ways to tell the story and process what happened can often be the first step.”