Does development benefit or break municipalities?

GUILDERLAND — Is growth actually good for a town?

If so, what type of land-use is best from a fiscal perspective?

Is there always a benefit to development? If there is, which of its 19 types gives a municipality the biggest return on its investment?

As Guilderland works to update its comprehensive land-use plan, and a discussion about a building moratorium is dragged out, while talk of another revaluation begins, the town wrestles with these questions.

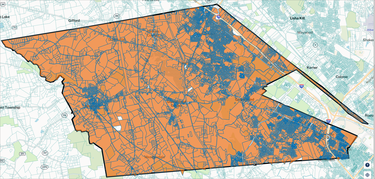

As New York is losing population faster than any other state in the nation, suburban Guilderland, with about 37,000 residents, is growing. The assessed value of the town’s approximately 12,200 properties, of which about 86 percent are residential, totals $4.5 billion.

During his state of the town speech in mid-February, Supervisor Peter Barber said 11 percent of residents’ property taxes go to the town; most goes to the schools. And soon enough, Barber said, “We’ll have to get into that ugly word of reval.”

Guilderland moved to full-value assessment in 1980 and had at first conducted townwide revaluations every four or five years. Guilderland last went through town-wide property revaluation in 2018 after a gap of 13 years, leading to a series of tax challenges, a number of which were successful.

Usage, dollars, density,

and development

Like most municipalities, Guilderland is trying to save for its future, while attempting to balance its short- and long-term goals against its wants and needs.

But “it’s very hard to plan for the future with the gun to your head,” according to Professor David Banks, who is a lecturer in geography and planning at the University at Albany in addition to being the director of its globalization studies program. He borrowed the phrase from a colleague who was referring to long-term planning at the university level.

Banks said, “If you’re constantly fighting for survival and to keep a budget in the black, just barely, you never have time to come up with any sort of interesting, outside-of-the-box kind of thinking.”

But with the update to its two-decade-old comprehensive plan, Guilderland has the opportunity to at least examine which types of development not only work best for the town but how they can best benefit it financially.

Working farms, studies have long shown, is the best type of land use for a municipality because “farmland has generated a fiscal surplus to help offset the shortfall created by residential demand for public services.”

But the results of those studies, known as cost of community services (CCS) studies, have also come into question because of the methodology used to conduct them, to the extent that researchers have found that “residential, commercial, and agricultural land all [have] indistinguishable relationships with the community budget.”

So, does development increase the taxbase more than it costs to service?

“In the short term yes, in the long term not always,” Banks told The Enterprise by email prior to a phone interview.

He said that new construction, housing in particular, increases in value in the short-term, but the “deciding factor,” he told the paper by email, “is density of the development and transit connections: higher density development with ample transit options will bring in more tax revenue than it costs to service.”

Single-family homes will increase in value, Banks said, but soon costs go up as well. Whereas with denser mixed-use development, it costs more in the short-term, because it’s more complicated to build and requires a larger upfront capital outlay, but retains value in the longer-term because a mixed-use building can have multiple uses and “several different lives,” said Banks, who cited an example from his home state to partially illustrate his point.

“I interned at the Sarasota, Florida County Planning and Economic Development Agency,” he said, and one presentation slide his boss always had him keep updated was called, “New Urbanism for Republicans,” and “it was pretty much all about taxes.”

Banks said the slide looked at a standard big-box store compared to a five-story mixed-use building and compared how much each cost a municipality versus how much a municipality received in revenue from each project type

“And it’s just — it’s miles away,” Banks said of the five-story mixed-use building. “It’s like tenfold more revenue than anything that a big box store will give you in its best years.”

Usage and density are dependent on zoning, effectively the reason for having a comprehensive plan.

Zoning, Banks said, “can get as fine-grained as” regulating the number of “units to the acre for housing.”

A goal of Guilderland’s comprehensive plan is to increase affordable housing. If zoning only allows for four to five units per acre, Banks said, “then you've effectively priced out any kind of affordable housing because the cost of land just makes it impossible to build anything affordable.”

Alternate revenue

While just 11 percent of Guilderland residents’ property taxes go to the town itself — most goes to schools — there are still ways to spare the taxpayer, with alternate ways of raising revenue.

Municipal broadband, which in some places can be as low as $10 per month for residents, is one way a city, town, or village can raise an alternate source of income.

Banks said Chattanooga, Tennessee, was a case study for the service.

He explained that a large light-industrial facility being built in the city necessitated an electrical system upgrade.

“They realized that they would have to lay fiber optic” to service the facility, he said. “And they’re like, ‘Well, if we’re already opening up the right-of-way to add all of this other infrastructure, we might as well just lay broadband and then sell access to it,” Banks said. “And that’s what they did, and it’s the fastest, cheapest internet in the country.”

New York State allows for municipal broadband.

He also pointed to Troy selling its water as another way municipalities raise revenue from sources other than property taxes, although the practice is not one that would work for Guilderland.

“We actually don’t have a lot of our own water here in Guilderland,” said Councilman Jacob Crawford during an October 2023 candidates forum. The town, he said, purchases water from the city of Watervliet, and from the city of Albany and the town of Rotterdam.

“We’re spending over a million dollars a year,” Crawford said.