On the homefront during the Great War: Patriotic rallies, Hoover dinners, shipping compresses and smokes

— Library of Congress

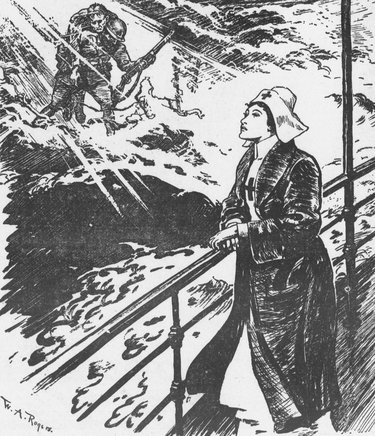

“The Call From No Man’s Land” was the caption on this May 10, 1918 newspaper picture accompanying a story on fundraising for the Red Cross, saying, “Every dollar spent alleviates misery.” It was printed in the Cottonwood Chronicle in Cottonwood, Idaho, similar to newspaper pleas that ran across the country.

The United States’ declaration of war on April 6, 1917 forced the American people to respond to the crisis of World War I. Guilderland residents met the challenge, giving overwhelming support to the nation’s war effort and to the troops shipped overseas.

Within days of the declaration of war, 200 people gathered in Altamont’s village park for a patriotic rally where the pastor of St. John’s Lutheran Church addressed the crowd, accompanied by selections played by the Altamont Band. American flags began to be flown on homes and businesses.

The reality of war was evident in Altamont when two weeks later a train of eight Pullman cars carrying 400 Marines, “a husky looking bunch,” passed through bound from Chicago to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Red Cross

President Woodrow Wilson, as honorary president of the Red Cross, appealed to citizens’ patriotism to help the Red Cross through monetary donations and volunteer activities in assisting the organization’s support of soldiers on the battlefield.

Additionally support was needed for its broader mission of sending supplies to prisoners of war and helping civilians, especially children, in the devastated areas of Europe. Wilson issued a summons during the week of Dec. 16 to 23, 1917 for everyone to enroll in the Red Cross, promising that every cent raised would go to war work.

Membership cost a dollar. Schoolchildren were reached through the Junior Red Cross. Several hundred people from Guilderland donated their dollars during the 18 months the United States was at war.

A variety of events were held around town specifically to benefit the Red Cross. In Guilderland Hamlet, “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” a patriotic cantata was presented at the Hamilton Presbyterian Church while in McKownville an entertainment was scheduled at the Methodist Church, admission 25 cents.

A movie night at Altamont’s Masonic Temple featured three reels, which not only depicted scenes of General John J. Pershing and the American Army, but also showed the vital work of the Red Cross “over there.” The show included patriotic songs as well, all for 20 cents.

A dancing party given at the town hall in Guilderland Center raised $100 from the 200 people who attended. These are just samples of fundraisers held at that time.

Volunteers in McKownville, Guilderland Hamlet, Guilderland Center, and Altamont pitched right in, quickly establishing Red Cross chapters in their communities with women in the nearby hamlets of Dunnville, Fullers, and Meadowdale working as part of these chapters.

The Red Cross meetings followed a regular schedule, either in private homes or in public places such as the town hall in Guilderland Center, Temperance Hall in Guilderland Hamlet, or Masonic Hall in Altamont, often lasting all day.

These women made huge amounts of materials to be sent periodically overseas to the Red Cross and lists of the many supplies that were shipped appeared in The Enterprise. Quantities included 333 compresses, 348 head strips, 25 sweaters, 18 pairs of wristlets, 244 handkerchiefs, 92 arm slings, 7 ambulance pillows and 10 hospital shirts.

These numbers represent amounts included in a single shipment. Pajamas seemed to be another big item. The production of these small groups of Guilderland women was tremendous, representing a huge contribution to the war effort if multiplied by women all over the country.

Tobacco Fund

Appealing to the generosity of its readers, The Enterprise opened a campaign in early October 1917 to send tobacco to soldiers overseas.

For a 25-cent donation, each serviceman would receive two packages of Lucky Strike cigarettes, three packages of “Bull” Durham tobacco, three books of “Bull” Durham cigarette papers, one tin of Tuxedo tobacco, and four books of Tuxedo cigarette papers, a value of 45 cents.

And in addition a postcard was included, which could be sent back to the donor thanking him or her. Week after week, the appeal was featured in the center of the front page illustrated by a large drawing illustrating soldiers gratefully receiving their smokes, often showing the Red Cross handing over the package, or soldiers puffing their cigarettes to keep them calm with shells exploding around them.

Names of donors and the amounts sent in were listed weekly for everyone in the community to see.

Although the editor admitted he had received some letters condemning the Tobacco Fund as immoral, it was felt the men really needed their smokes on the battlefield.

One headline read, “Physicians Endorse the Tobacco Fund for the Soldiers,” while an anonymous officer was quoted, “My men will bear any dirt or discomfort as long as they are supplied with smokes.”

One week’s appeal stated the men were just as dependent on cigarettes as they were on food. “The loud uproar of battle, the discharge of the heavy guns, the bursting of enormous shells and the charge of the yelling battalions are enough to send the average man to the ‘insane ward,’” with the implication that their smokes would help them through this ordeal.

The whole idea originated with the American Tobacco Company in what was really a clever and lucrative marketing scheme, getting the newspapers to collect the money and the Red Cross to deliver the cigarettes to the front lines.

The name of the company involved only came out when they were forced to send out a letter a few months later to be published in all these newspapers apologizing, offering an explanation as to why none of the donors were receiving their thank-you cards.

They claimed the tobacco had been shipped to France, but the rail lines to the front were so congested that the tobacco was piling up in port. Eventually a response was received by a Meadowdale man that said, “I received your tobacco today and was more than thankful for it.”

The campaign came to an end May 1, 1918 when the American Tobacco Company notified newspapers they were discontinuing the Tobacco Fund since the U.S. government was taking their entire output of Tuxedo and “Bull” Durham tobacco.

During the course of the campaign, The Enterprise had received $133.50 donated to the Tobacco Fund and in addition, had received much advertising for Lucky Strike cigarettes and “Bull” Durham tobacco.

Anti-German sentiment

Anti-German emotions ran high in part because the United States government created the Committee for Public Information to spread anti-German propaganda.

The Enterprise ran a series of 15 articles obviously coming from an outside source with such titles as “Diaries of German Soldiers Tell of Murder and Pillage in Belgian Cities” and “Germany Guilty of Barbarities in War Conduct.”

In a cartoon supporting a bond drive, a hapless dachshund wearing a German officer’s helmet represented the enemy.

Altamont High School was one of many American high schools that removed German language from its curriculum.

Ads appeared in The Enterprise for some time paid for by the American Defense Society, headlined “To Win This War German Spies Must Be Jailed.” Listing a New York City address and endorsed by an advisory board including former President Teddy Roosevelt, the group requested a donation for membership and urged readers to ”telegraph, write or bring us reports of German activities in your district.”

Germans were frequently referred to as Huns or Boche in print or picture.

Cutbacks in food and fuel

Changes intruded on everyday life. For the first time ever, daylight saving time was instituted to save fuel.

In early 1918, fuel-less Mondays were attempted. The D & H ran its limited Sunday schedule again on Monday as well, which meant Altamont High School remained closed on Monday and rescheduled classes for Saturday because so many of their students commuted by train and couldn’t get there on the revised Monday schedule.

Local businesses closed down, although grocery stores were exempt.

January 1918 was the coldest since the Albany weather bureau was founded and the ice on Black Creek near Osborn’s Corners where the Tygerts cut ice blocks was reported at 38 inches thick. Local temperatures were reported as low as -26 degrees.

However, at Masonic Hall, a special “Fuel-less Holiday” five-reel movie program was showing for only 10 cents. Fuel-less Mondays were impractical and were soon discontinued.

Another inconvenience was learning to do with less wheat, because huge amounts were diverted to Europe to feed troops and starving civilians. Recipes appeared in The Enterprise for substitutes like biscuits made with parched corn meal and peanut butter or for potato cutlets!

For a time “Hooverize” became a new word in American’s vocabulary. A major aspect of Hooverizing was meatless Mondays and wheatless Wednesdays. One slogan was, “When in doubt, eat potatoes.” An Altamont bakery offered some wheatless alternatives.

St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Guilderland Center even ran a Hoover dinner, named after Herbert Hoover, appointed head of the U.S. Food Administration.

War bonds

Citizens were asked to share the country’s financial burden of the war by buying bonds. In the 18 months that we were involved in the war, the government sponsored four Liberty Loan bond drives, assigning a quota to be reached by each community.

Committees were set up, and usually a patriotic meeting or rally kicked off the drive to psych the people to subscribe for bonds. Bond purchasers’ names were published in The Enterprise as well as the dollar amount pledged.

Quotas always seemed to be exceeded, at least in part because it would have been an embarrassment to you and your family to have your name missing from the list. In the Fourth Liberty Loan drive, the quota for Altamont and vicinity was $40,000 and this after three previous quotas had been met and exceeded.

During the Fourth Liberty Loan drive a special “Yankee Trophies” train of eight Pullman cars and some flat cars stopped in Altamont on its way along the D & H line. Captured German field guns and other large articles of war were displayed on the flat cars while inside the Pullman cars observers could walk through, inspecting German helmets, machine guns, gas masks, and hand grenades.

After their opportunity to view the battle souvenirs, people were to attend a huge rally when they could make pledges to buy bonds. The quota was passed in spite of the Spanish influenza epidemic spreading through town at the same time.

Simultaneously large ads were running in the paper promoting the fourth bond drive each with the name of many local businesses such as Altamont Bakery, Becker’s Livery, and CJ Hurst down at the bottom as sponsor. Publicity and peer pressure surely played a part in getting people to support these bond drives.

Draft

Much newspaper space was given over to news of the draft after the Selective Service Act was passed on May 17, 1917. Lists of eligible men and locations where they were to report were prominent local news.

The newsy columns from Altamont and the other hamlets of the town often contained names of men who either had left for training camps, left for overseas, or were home on leave.

Whenever correspondence penned by a local serviceman was shared with The Enterprise, it was printed, giving the local population a personal glimpse of the front lines “somewhere in France.”

J.H. Gardner Jr. of Meadowdale actually sent home a war souvenir German helmet, put on display for a few days in the Enterprise office.

Guilderland Center’s Dr. Frank H. Hurst, one of the first to arrive overseas, was initially assigned to a British field hospital and later was in command of an American field hospital. Wounded twice and then gassed, he was a prolific letter writer and several of his lengthy descriptive letters, one of which was written on captured German paper, were shared with newspaper readers.

Fortunately, on Nov. 11, 1918, eighteen months after the United States entered the war, it was over.

Life in Guilderland quickly returned to normal, but for the young men who actually were part of the trench warfare “somewhere in France” things would never be quite the same.