Jerry's Law passes

Enterprise file photo — Marcello Iaia

Mary Clark displays, earlier this year, a tattoo she had made to remember her grandson, Jerry Clark III, whose 2010 suicide inspired Jerry’s Law, which was signed by the governor last week. The tattoo illustrates a torn and shredded heart and notes the date of his death. Clark said that she spearheaded the legislation to protect other students and inform families of their rights for special-education services evaluations in schools.

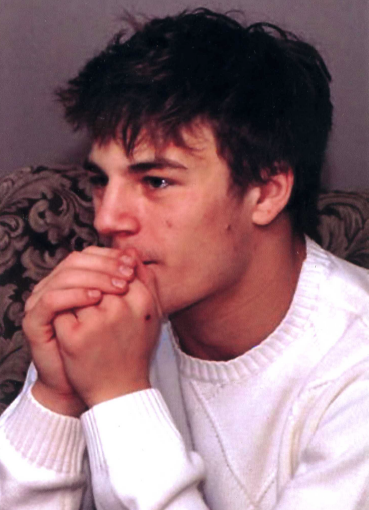

Photo from Mary Clark

A grandmother’s favorite photo: The 2010 suicide of Jerry Clark III, seen here in a photo submitted by his grandmother, Mary Clark, inspired legislation known as Jerry’s Law, which now requires schools to inform parents of their right to have their child evaluated by their school’s Committee on Special Education.

VOORHEESVILLE — Mary Clark described the passage of Jerry’s Law, signed by the governor last week, as an event resulting from divine intervention.

The law Clark and her son, Jerry Clark II, championed requires schools to inform parents of their right to have their children evaluated by the Committee on Special Education.

Clark is the grandmother of Jerry Clark III, who killed himself in April 2010. Her grandson suffered from emotional issues, and received medical care, which included anti-depressant and mood-stabilizer prescriptions, all while he continued to attend Clayton A. Bouton High School in Voorheesville, Clark said.

While in high school, Jerry Clark III instigated several incidents, the school said, which resulted in a school suspension, his removal from the school’s wrestling team, and a superintendent’s hearing.

“Superintendent’s hearings are only for egregious violations of the code of conduct,” said Superintendent Teresa Snyder previously.

Jerry’s Law

“The bill was actually signed by the governor,” Mary Clark told The Enterprise. “For an education bill to be passed in both houses and [signed] by the governor is rare.”

Governor Andrew Cuomo approved the bill on Nov. 21.

“I’m basking in my gratitude — gratitude to everyone who supported this bill,” Clark said.

Clark is the community liaison for the school district’s Risk Behavior Task Force, she said. The group formed to assess how to keep children from making bad decisions about alcohol and drug use, but now also includes a focus on mental health, Clark said.

She cited a statistic stating that 1 in 5 children have mental-health issues. Of children ages 9 to 17, according to the United States Department of Health and Human Services report, “Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General,” 21 percent have a diagnosable mental or addictive disorder that causes at least minimal impairment.

Clark, herself, is giving parents and local residents papers outlining the benefits of Jerry’s Law, she said.

“Under the law, [districts] weren’t accountable. Now they are,” Clark said about notifying parents of available services.

The Voorheesville Central School District has not been cooperative in getting Jerry’s Law passed over the last four years, Clark said.

“They were against the bill,” she said.

“Nobody came to the school board and asked for the board’s support,” Snyder said this week. Proponents for the bill were “never” on the school board’s agenda, she said.

“The school does anything the school can to help children be successful. Our job is to make certain that they are successful, to the extent that they are able to be,” Snyder said.

She also said, “We hold kids accountable.” Districts must provide “a safe place for all children,” she said.

“I feel that the law is redundant,” Snyder said about Jerry’s Law. New York State has a high identification rate of students who require special-education services, she said. Statewide, 17.8 percent of students are identified as needing special services, according to data from the State Education Department for 2012-13; Voorheesville identified 10.7 percent of its students as needing special-education services, which is typical for school districts in its socio-economic group. East Hampton (Suffolk Co.), for example, identifies a similar percentage of children as needing services.

Although Jerry Clark III had mental health issues, he was not identified as needing special-education services. Snyder had said earlier that special-education services are not for emotional issues.

“The school’s focus is on school,” she said previously. “We are an educational enterprise, not a mental-health facility.”

The new law, which amends current education law, states that, when a child is enrolled in a public school, the child’s parents would be informed of their rights “regarding referral and evaluation of their child for the purposes of special education services or programs.”

Parents can be directed to the State Education Department’s website for information, and the notification from the school is to include the name and contact information for the person who chairs the school district’s Committee on Special Education or who is charged with processing referrals to the district.

With the passage of the additional law, Voorheesville will follow the rule, Snyder said.

“No harm, no foul,” she said this week. “There may be some fundamental misunderstanding about what schools provide.

“We provide home-tutoring with a doctor’s note,” Snyder continued, referring to all public schools in New York. “It’s not a special-education service. It’s a regular-education service provided because a doctor notifies us that the child needs it.” This applies to students with mental health problems as well as physical ailments.

“We don’t have staff to provide people who are credentialed to provide mental health services,” Snyder said. “We follow the doctor’s orders. That’s true of any ailment — any health issue. We work all the time with outside agencies. We also consult our own physician that is on retainer for the district. Every school in the state has one.”

Mary Clark said that she will continue to push for awareness among students and parents about mental-health issues, now that the bill has passed.

Asked if she would continue to advocate for mental-health issues, Clark said, “This looked like the end. It may be just the beginning.” Clark called Assemblyman Harvey Weisenberg and New York Senator John Flanagan “true champions” for sponsoring the bill.

She knows them well now, she said, noting that she took them cannoli in a move that her son called unprofessional, but which drew their attention.

“I only know them from knocking on doors,” Mary Clark said.