Don't get hung up on an image, understand the big picture

Every week, we make decisions about what news is most important to cover; we are limited by staff time to investigate and by newspaper space. Our most important stories run on the front page.

The last week in May, after the Guilderland High School yearbook came out, we started getting calls and emails from people upset about a picture in a yearbook ad. Parents of Guilderland graduates have, over the years, surprised their children by taking out ads in the yearbook — frequently with pictures important to the family and words of advice or praise.

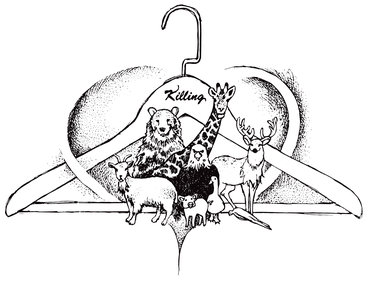

The ad that some were upset about pictured a boy standing next to a giraffe he had presumably shot. The caption under the picture read, “A hunt based only on the trophies taken falls far short of what the ultimate goal should be.”

We decided to spend our time and space that week, for Guilderland school coverage, on two other stories — one on Moody’s downgrading the district’s credit rating, and the other, a front-page story, on two newly ratified contracts. While most of the local media covered the yearbook story, these were two stories no one else has yet covered and we believe they are more important. Guilderland residents should be informed about what, through taxes, they are paying school employees, and also how the district is handling its finances.

The next week, we ran a front-page story on the latest in a decades-long series of projects that Alan Fiero, a science teacher at Farnsworth Middle School, has spearheaded to educate his students about the Karner blue butterfly, which is on the federal list for endangered species.

We thought, if we could talk to the family who had taken out the yearbook ad, that might be a worthwhile story to print. No one had told their side of the story and, through social media, the family was getting pounded.

When we interviewed Superintendent Marie Wiles, she outlined the process the yearbook staff — students overseen by advisors — had gone through. The printed yearbook ads had all followed established guidelines and no one had anticipated the reaction to the ad with the giraffe so it had not been reviewed by administrators like other matters that had raised questions or concerns, said Wiles.

Wiles said further she “lost a week,” responding to media and others’ concerns over the ad. In the future, she said, an administrator will review the entire yearbook; Wiles said the yearbook is big and lamented the loss of time for already busy administrators.

Because we didn’t want to run a one-sided story, and we couldn’t reach the boy’s family, we asked if Wiles could contact them to see if they would talk to us. “The family is interested in putting this behind them and is worried that their comments would just stir things up,” Wiles wrote us in an email after contacting the boy’s father.

The school district prominently posted an apology on its website stating that “the district would like to apologize to those offended by the photo.” The apology went on, “We are actively reviewing our yearbook submission protocol as well as yearbook administrative review policies, to ensure issues like this are avoided in the future. The yearbook is not meant to be a platform for controversy; it’s a vehicle for celebration and capturing memories.”

We don’t believe the school district did anything wrong. The yearbook staff allowed the family to exercise its First Amendment right to free speech, celebrating their son in a way their family values.

We have had similar responses when we at The Enterprise have published pictures in our sports section submitted by hunters photographed with the animals they have killed. We believe a newspaper should accurately reflect the community it serves — all parts of it.

Few people submit such pictures anymore because of the often nasty reaction. The last picture we recall printing was when the grandmother of a 17-year-old who killed a 350-pound black bear submitted a picture of her grandson with the dead bear. She said of her grandson, “He was just out there all by himself.” The bear, she said, “filled his scope with black.” She also said the bear’s meat would be eaten and its head would be mounted.

The week before, we had run a front-page story that included a picture of the owner of a local slaughterhouse pointing to some goat carcasses. We didn’t get a single letter or phone call objecting to that. But we were swamped with protests and complaints over running the picture of the 17-year-old with the bear he had killed.

We wrote then about the work of Konrad Lorenz, the pioneering and world-renowned scientist of animal behavior. He began his 1949 book on man and domestic animals with these words, “Today for breakfast I ate some fried bread and sausage. Both the sausage and the lard that the bread was fried in came from a pig that I used to know as a dear little piglet.”

Most of us eat meat or wear leather shoes or belts or coats, or take medicines that come from animal parts. But most of us do not kill the animals we eat. Our food comes neatly packaged in the grocery store. Our leather comes in shoeboxes; we don’t have to kill the animal and scrape its hide. Our medicine comes in bottles or pristine tablets. And, as we wrap ourselves in down to stay warm, few of us think about the dead geese that made our jackets or comforters. We don’t have to wring their necks and pluck them.

Lorenz does not let himself off the hook so easily. “It is, of course, hypocritical to avoid, in this way, the moral responsibility for the murder,” he writes.

In his book, “Man Meets Dog,” Lorenz writes that a farmer is bound by no contract with domestic animals to treat them as anything but enemies he has taken prisoner. Referring to his own situation as a scientist, Lorenz goes on, “But for the man who is engaged professionally in research into the animal mind which, in its inmost workings, so much resembles our own, the matter assumes an entirely different aspect. For him, the slaughtering of a farm animal is something infinitely worse than the shooting of game. The hunter does not know the latter personally or, at least, not so intimately as the farmer does the domestic animal and, above all, the game animal recognizes the danger it is in.

“Morally, it is much worse to wring the neck of a tame goose which approaches one confidently to take food from one’s hand than it is, at the expense of some physical effort and a great deal of patience, to shoot a wild goose which is fully conscious of its danger and, moreover, has a good chance of eluding it.”

Therein lies a distinction that escapes those who object to hunting.

The story of the yearbook ad with the slain giraffe was covered not just locally but picked up by the New York Daily News. The comments on that tabloid’s site as well as on local media excoriated the boy and his family, calling them “morons,” and “sick individuals,” and stating, “They are trash.”

Because we couldn’t talk to the boy’s family, we don’t know the circumstances of the hunt. We do know that the International Union for Conservation of Nature, a respected organization that works for sustainable use of natural resources, has listed the giraffe species as a whole as a species of “least concern.” Three sub-species of giraffe are in decline or endangered — the West African giraffe, Rothschild’s giraffe, and the reticulated giraffe. If the boy shot one of these, criticism is warranted.

We find it far more likely, however, that he was part of a monitored, legal hunting expedition where animal populations are controlled — as in New York State, say, for deer — by encouraging hunting of specified animals. Old and sick male giraffes are allowed to be killed so younger males can breed, allowing the herd to grow, according to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation. The foundation also has found that, in addition to poaching, the overall decline in giraffe population is due to human population growth, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, and habitat degradation.

Earlier this spring, comedian Ricky Gervais created an online firestorm when he posted a five-year-old picture of Rebecca Francis lying next to a giraffe she had killed. Francis, a hunter who has been featured on “Eye of the Hunter,” an NBC Sports Network show, received death threats after the post.

“When I was in Africa five years ago, I was of the mindset that I would never shoot a giraffe,” she told Hunting.Life.com in a statement posted on its Facebook page, “I was approached toward the end of my hunt with a unique circumstance. They showed me this beautiful old bull giraffe that was wandering all alone….He was past his breeding years and very close to death.

“They asked me if I would preserve this giraffe by providing all the locals with food and other means of survival. He was inevitably going to die soon and he could either be wasted or utilized by the local people. I chose to honor his life by providing others with his uses and I do not regret it for one second. Once he was down, there were people waiting to take his meat. They also took his tail to make jewelry, his bones to make other things, and did not waste a single part of him. I am grateful to be a part of something so good.”

We’ve come a long way, in America, from a culture that uses every part of an animal. We’ve tampered with the very nature of the animals themselves. Some cows are now raised so that they never set foot on, let alone graze on, grass. Some chickens are bred so that their breasts are so heavy they can’t walk. Some domesticated animals suffer their entire lives, at the hands of humans, until they are slaughtered.

A wild animal can lead a good life until the moment it dies. And, if the hunter who kills it is human, he at least has respect for and knowledge of the animal and its natural habitat. Hunters haven’t altered the nature of animals they’ve killed. Hunting organizations have done much to restore natural habitats and re-introduce near-extinct species.

We humans have tampered with the natural world to such an extent that “wild” animals exist only with careful controls. A good hunter, a hunter who follows the rules, needs a license to kill and can only take certain game at certain times. Poachers are a different matter and should be prosecuted.

Worse forces than hunters’ bullets threaten the Earth’s wildlife. Each year, dozens of species disappear forever from our planet, threatened by the force of development — the pollution of water, land, and air — and climate change brought about by humans.

In his Nobel Lecture on analogy as a source of knowledge, Lorenz said, “Human culture, after enveloping and filling the whole globe, is in danger of being killed by its own excretion, of dying from an illness closely analogous to uraemia. Humanity will be forced to invent some sort of planetary kidney — or it will die in its own waste products.”

We doubt the panacea of a planetary kidney can save us. Hard choices and sacrifices must be made to preserve our planet. Symbols can be as powerful as analogies; they can inspire us.

The bald eagle is a longstanding symbol for America, which has taken on added meaning in New York State as a symbol of humans, through science and hard work, restoring what we nearly destroyed.

This month, the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation reported a 38-year-old bald eagle was found — the oldest banded bald eagle in the nation, by five years. He was apparently hit by a motorist; vehicle collisions account for about a third of eagle deaths in New York.

Number 03142, as the DEC wildlife biologists call him, is a symbol of success in conservation. In the 1970s, the state had just one remaining unproductive bald eagle nest, on Hemlock Lake in Livingston County.

Following a national ban on the chemical pesticide, DDT, which weakened the eagle’s eggs so they wouldn’t hatch, and prohibitions against killing bald eagles, New York started a restoration project in 1976.

Over the next five years, 23 fledgling bald eagles from Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge in Minnesota were released in New York. Number 03142 was one of them; he was banded in 1977 and he began nesting in 1981 at Hemlock Lake where he became a father to many eaglets over the course of three decades. The resident male of the state’s last native pair of eaglets at Hemlock Lake was found shot to death n 1980.

But the hacked, or transplanted, eagles flourished in New York and today the state supports 350 pairs of nesting bald eagles.

But the restoration of one species is just the beginning of work that needs to be done. A State Wildlife Action Plan, meant to protect rare and declining wildlife species, is now available for public comment. The 10-year plan identifies 366 Species of Greatest Conservation Need in New York — from the big, like the moose, to the small, like the barrens buckmoth.

We can make a difference, right here in our state, if we put the sort of energy that went into criticizing a yearbook ad into preserving habitats that will keep more species from extinction. Except for harm done by illegal poachers, most of the giraffes in Africa are closely protected with hunting allowed only where it will help the herd.

A local symbol comes to mind — a fragile and fluttering blue symbol — which brings us back to where we started, with our choice to run a front-page story on Dr. Fiero’s students learning about the Karner blue butterfly.

Over the years, his students have not only learned an appreciation for the natural world and their place in it, they have done hands-on work in the Pine Bush Preserve, girdling aspens, and invasive species, so lupine essential to the Karner blue, can flourish. His students have also worked on artificial rearing of the butterflies, and they’ve encouraged community visitors to their summertime Butterfly Station to put native plants in their yards and gardens.

When Dr. Fiero started bringing his students to the Pine Bush Preserve 20 years ago, the butterflies numbered in the hundreds. “Now,” he said, “they’re in the thousands.”

Let us seek to understand rather than condemn, and to put our energies to productive use.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor