Preventing harassment can be a matter of life or death

Numbers can numb us.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Americans aged 10 to 24 — some call it the “Silent Epidemic.” (The first cause is unintentional injury.) According to a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease control in 2013, more than one out of every six students responded they had “seriously considered suicide in the past twelve months” and more than one out of 13 reported attempting suicide within the same time period.

Adolescents make up roughly a fifth of all Americans — over 64 million — and in the past decade those between the ages of 10 and 24 has grown by 7 percent.

That makes for a lot of young people contemplating, attempting, and even succeeding at suicide.

For us, the epidemic is not silent. A courageous voice has been raised to inform us. Mackenzie Dunnells, a 12-year-old from Berne, visited our newsroom with her mother, Paula Dunnells, and told us what it felt like to want to kill herself.

Her voice was quiet and her blue eyes were wide as she told us, “I got this overwhelming feeling, thinking about all that had been done for five years at school and no one listened to me,” said Mackenzie.

She is a student at Berne-Knox-Westerlo in the rural Helderberg Hilltowns and says she started being harassed when she was in the third grade. On the day she tried to kill herself, Jan. 12, she was called a “f------ bitch,” she says.

She and her mother related a series of incidents, detailed in our front-page story, that included being beaten with a hockey stick, requiring medical attention; being shunned by girls who once were her friends when a ringleader told them not to talk to Mackenzie; and being called names like “whore” and “slut.”

Mrs. Dunnells says that, over the years, as she has talked to teachers and administrators about these assaults, she was often told that, since a teacher hadn’t witnessed the affront, nothing could be done.

This led us to look closely at the Dignity for All Students Act, which was signed into state law in 2010 and took effect in 2012. A resource guide on the Dignity Act put out by the State Education Department had more numbers. But we no longer felt numbed by the startling numbers — startling because the percentages are so high — since we could see Mackenzie in each of them.

In descending order, the guide reported on a student survey that said 79 percent said they had seen bullying or name-calling on their school playgrounds — one of the main places where Mackenzie says she suffered, retreating to a corner to cry.

Fifty-four percent said they had seen bullying or name-calling in their school cafeteria, and 39 percent on the school bus — other places Mackenzie says she was affronted; her parents started coming to school to eat lunch with her, and drove her to and from school so she wouldn’t have to take the bus.

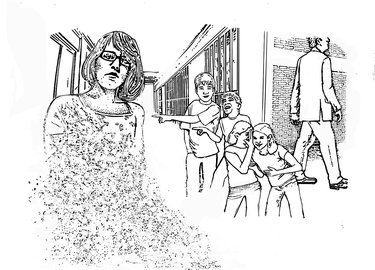

Forty percent said they’d seen such behavior in school hallways; that’s where Mackenzie says she was purposely shouldered and kicked. Thirty-seven percent said they saw bullying and heard name-calling in school classrooms; that’s where Mackenzie says her tormenters would pretend to drop something like a pencil near her desk so they could crouch next to her to say something mean.

The guide also charted the frequency of help students said they received if they told a teacher about being made fun of: Just 11 percent said they received help “all of the time.”

So Mackenzie is not alone. This is in direct contradiction with the law. The Dignity Act requires that the school principal, the district superintendent, or their designees lead a thorough investigation of all reports of harassment, bullying, and discrimination and ensure that such investigation is completed promptly after receipt of any written reports of harassment, bullying, and discrimination.

The self-reported data that schools across the state are required to send to the State Education Department shows that, for the last school year, the elementary school in Berne reported three incidents of discrimination or harassment and the secondary school reported 26. The year before that, the elementary school reported zero — this is when Mackenzie was a student there and says she was harassed — and the high school reported 21. In 2012-13, the first year records were required when, again, Mackenzie was an elementary student, both BKW schools reported there were zero incidents of harassment.

The guide quotes from a module developed by the United States Department of Education National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments: “It is important to respond to reports of bullying whether you witness the behavior or a student reports it to you.”

This means the excuse Mrs. Dunnells said she heard time and time again — the teacher didn’t see it and so couldn’t do anything about it — is invalid.

The federal module outlines guidelines called the “Five Rs”:

— Respond: When bullying is reported or witnessed, the teacher is to intervene immediately, reassuring the student who has been bullied that it is not his or her fault;

— Research: The allegations are to be documented, with accounts from as many sources as possible, including bystanders, to determine whether the incident was indeed bullying or another kind of negative or aggressive interaction;

— Record: Everything should be collected and saved in a folder;

— Report: Guided by a school’s policies and the commissioner’s regulations, a thoroughly researched report, including review of the school’s code of conduct, would determine whether the incident is bullying or another form of behavior; and

— Revisit: After a plan is developed for both the student who was bullied and for the student who engaged in bullying behavior, each student should be checked on to find out if the plan is working and if more needs to be done.

The guide recommends restorative justice rather than a punitive approach, and notes that victims of bullying can often become bullies themselves.

Judging by the Dunnells’ account, the one time anything close to the “Five Rs” approach was used with Mackenzie was when she was accused of threatening to shoot an aid; an investigation with bystanders’ testimony proved the allegation wasn’t true, the Dunnells said.

We don’t blame Mackenzie’s parents for wanting their daughter out of the school system that has hurt her so badly. “It makes me feel like I’m nothing,” Mackenzie said of being bullied. But we hope the school district uses this crisis as an opportunity to take a close look at its policies and procedures. The student handbook says what the law requires but, unless those words are heeded, they do no good.

Within the year, we’ve written of two other incidents at Berne-Knox-Westrlo where students felt harassed and, worse, then felt ignored by school leaders. Last March, a 12-year-old girl told us how hurt she was to be called “nigger.” And, several months before that, we heard from a group of girls who felt uncomfortable because an authority figure at their school touched them in ways they did not like.

The district has suffered from several years of leadership turnover — two one-year interim supervisors, and migrating school principals as well.

The current superintendent, Timothy Mundell, new this summer, says he is at BKW for the long term and reports positive changes already with the new leadership team. We were heartened by his report that, comparing data from the first quarter last year to this year, attendance has improved, disciplinary referrals are down, and academic scores are on the rise.

That is welcome news. With such solid ground, we urge the new BKW leaders to take a close and deep look at how harassment is handled. Go beyond the superintendent’s blanket statement, “Whether this year or in years’ past, we’ve always taken seriously any allegations and investigated them…We act on these things.”

As the state’s guide points out, a school’s climate and culture must be evaluated — safety in an emotional environment is as important as in physical environment. It may be far easier to, say, fix a buckled floor, than recast a school culture. Insisting everything is fine and always has been isn’t going to help students who are suffering, or teach the right lessons to students who are aware of the bullying as bystanders.

“Teaching social and emotional skills is as important as teaching academic skills,” says the state’s guide. The law says that, whether a student is being bullied himself or herself or has witnessed another student being bullied, she or he needs to feel empowered, comfortable, and safe reporting such an incident to school faculty or staff.

Creating a culture where that happens and where the staff then responds is essential — it’s a matter of life or death.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer