— Photo from Postdlf

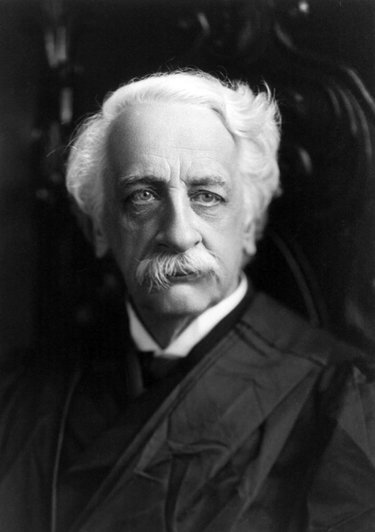

Rufus Wheeler Peckham, who lived from 1838 to 1909, is buried in Albany Rural Cemetery in Menands. There is also in that plot a cenotaph or marker for Peckham's father, New York State Court of Appeals Judge Rufus Wheeler Peckham, and his stepmother who were lost in the sinking of the Atlantic steamer Ville du Havre in 1873. The elder Peckham was also a prominent Albany lawyer.

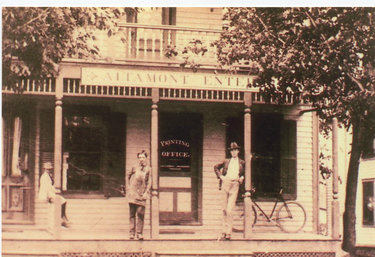

The Enterprise — Melissa Hale-Spencer

Coolmore, Rufus Peckham’s summer home, where he died in 1909, was bought by Bernard Cobb, a utilities magnate, who named it Woodlands. After Cobb died in 1957, his daughters donated the property to the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary who ran the Cobb Memorial School there for children with disabilities, adding modern buildings and a playground to the campus. The 65.3-acre property (most of it in Guilderland with about 13 acres in Knox) has a full-market value of $2.7 million, according to the Albany County assessment rolls. Although the Cobb Memorial School is now closed, “The property is not for sale. The sisters use it for retreats and vacations,” said Marcia Hansen, reached at the sisters’ Haswell Road location in Watervliet. “They’re there all the time.”

Who was Rufus Wheeler Peckham?

The short answer is: A United States Supreme Court associate justice.

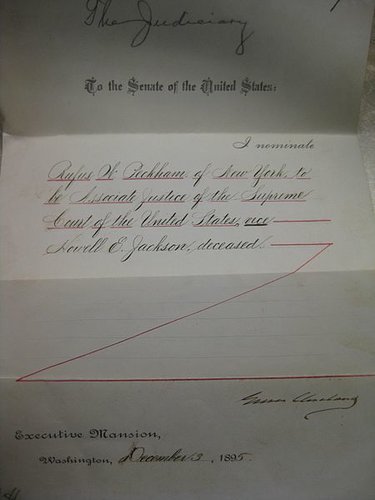

He was appointed in 1895 by Democratic President Grover Cleveland; his confirmation followed six days later by a voice vote of the Republican majority Senate — the last time for this political occurrence.

Rufus W. Peckham is making an appearance in The Enterprise because he happened to be an Albany native, a member of the city’s wealthy, prominent elite, who was also a longtime resident of Altamont’s summer colony.

Born in 1838 to a father who was a very successful, well known attorney and judge, Rufus Peckham received a classical education at Albany Academy, then traveled to Philadelphia for additional studies. After a lengthy tour of Europe accompanied by his brother, he returned to Albany where he resumed his studies. Admitted to the bar in 1859, he joined his father’s law firm, beginning a very successful legal trajectory that ended at the summit of an attorney’s career.

His private clients, being chiefly banks, insurance companies, and corporations such as the Albany and Susquehanna Railroad, earned him a reputation for being an effective attorney who almost always won his cases. He was reputed to be on personal terms with such moguls as J. Pierpont Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and John D. Rockefeller. In later years, as he served on the New York State Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, and then on the U.S. Supreme Court, he definitely seemed to favor business interests.

Within 10 years of joining his father’s firm, the young lawyer became district attorney for the city and county of Albany. In addition, he served as special assistant to the New York State Attorney General from 1869 to 1872. During these years, he dealt with a series of criminal cases where his success at trial proved to be equal to his competency at corporate law.

In spite of his busy legal commitments, Peckham was a staunch Democrat, becoming acquainted with prominent politicians, and was especially friendly with Governor Grover Cleveland in the years before his election to the presidency. Peckham served as a delegate in both the 1876 and 1880 Democratic conventions.

In 1883, he was elected to the New York State Supreme Court, the lowest court in the state’s three-tiered system. Three years later, he became a judge of the Court of Appeals where he remained until his 1895 appointment to the United States Supreme Court. At that time, Peckham is supposed to have exclaimed, “If I have got to be put away on the shelf, I supposed I might as well be on the top shelf.”

Coolmore

Personally, Peckham was described by his contemporaries as “vigorous, of forceful character, frank, and outspoken.” Physically, he was described as having a “cameo face and piercing eyes,” while in company he was considered “an agreeable, entertaining conversationalist.”

Married in 1866 to a New York City woman, Peckham became the father of two sons, Rufus Jr. and Henry, always called Harry. The family home was on Albany’s lower State Street adjacent to St. Peter’s Episcopal Church.

In 1884, when his sons were in their teens, Peckham’s decision to acquire a large tract of land brought the family to the escarpment above Knowersville. After the construction of the Peckhams’ large summer home, sometimes referred to as a “villa” in The Enterprise, the name “Coolmore” was given to the estate.

The spectacular outlook from the property, described by Fletcher Battershall, a friend of Peckham’s sons who had been a frequent guest at Coolmore, was an “unbroken view of the valley of the Hudson stretching to the foothills of the Berkshires,” while “behind stretches the rocky Helderberg tableland, rolling and diversified by woods, farms, and isolated hamlets.”

It was “an ideal place for growing boys and their pleasures,” and the Peckham sons were welcome to entertain their young friends as regular visitors at the estate. Summer neighbors included other wealthy and well-connected Albanians James D. Wesson, Mrs. William (Lucie) Cassidy, and Charles L. Pruyn who also had children.

In those early years, a steady stream of guests were entertained at Coolmore, stirring the recollection of the Peckham sons’ friend who reminisced, “There were good times on the hills of Altamont.”

In one instance, Harry and Edward Cassidy imported Belgian hares, let them go in the surrounding woods and fields, inviting their young adult friends to pursue the hares with a pack of beagles. At other times, they hunted raccoons by moonlight. Much tennis was played and exploration of the nearby countryside was another pastime.

The summer colony’s attractions not only included lovely scenery, healthy air, and pure water, but its location was easily accessible, only an hour away from Albany on the frequently scheduled D&H locals. Commuting was feasible for those with professional or social commitments in town. D&H Conductor Joseph Zimmerman, obviously highly thought of by regular riders, was gifted with “a beautiful conductor’s lantern with his name neatly inscribed.” Among the contributors was Judge Peckham.

Judge Peckham apparently purchased his tract of land not solely as the site of a summer home, but also for a farm to be supervised by a local farmer, particularly to provide a sizable hay crop. Having had a strictly urban background, Judge Peckham while inspecting his farm during haying season one day was puzzled by the piles of grass all over his fields. It had to be explained to him that it wasn’t refuse littering his land, but freshly cut hay drying before being taken to the barn.

Peckham, like the other wealthy summer colony residents, provided employment for local men on his property and patronized nearby businesses, earning the good will of Knowersville’s (as Altamont was called until incorporated in 1890) residents and certainly helped to boost the village’s economy.

Men were hired for farm work and as farm managers and, in addition, an estate supervisor was employed. The names of various men who worked for the Peckhams were often mentioned in the Enterprise’s village column.

Note was also made that lumber for an 1895 expansion of the Peckhams’ cottage was being supplied locally and at least one wagon was purchased in the village. And at the end, the services of the Altamont doctor and undertaker were provided.

What’s in a name?

A few years after the Peckham family became regular summer residents, there was difficulty with mail delivery, due to the name Knowersville being frequently confused with a village in the western part of the state having a similar name, leading to a movement to rename the community.

A piece appeared in The Enterprise asking, “Shall it Be Peckham?” offering the suggestion that the village should be designated “Peckham” in Rufus’s honor. After all, the writer argued, he was a Court of Appeals judge; “Peckham” was easier to write than “Knowersville”; and besides, the judge might “honor himself and the village in some substantial manner.” It ended with, “By all means, let it be called Peckham.”

A protesting, upset citizen responded a week later, representing a faction not in agreement with the thought of living in Peckham, New York. Very shortly, the discussion became a moot point because Lucie Cassidy had used her influence with President Cleveland to rename the village Altamont.

Upon becoming a Supreme Court justice, Peckham sold his Albany home, moving to Washington, but he continued to summer each year at Coolmore where he died in 1909.

Laissez-faire decisions

As an associate justice on the Supreme Court, he was best known for writing the majority opinion Lochner vs. New York State in 1905 when the court ruled, 5 to 4, that the New York Bakeshop Act, a law prohibiting bakers from working more than a 10-hour day, six days per week, was unconstitutional.

Peckham’s opinion put forth the argument, “The freedom of master and employees to contract with each other … cannot be prohibited or interfered without violating the 14th Amendment.” This case has been mentioned unfavorably in mainstream newspaper and magazine articles about the Supreme Court in recent years and on occasion Peckham’s name is also mentioned.

Peckham also voted with the majority in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson in 1896, upholding the constitutionality of southern Jim Crow laws.

Justice Peckham, who considered himself a strict constitutionalist, is today remembered by legal scholars and students of the Constitution as a “nonentity, “a pygmy of the Court,” his reasoning described as “unfathomable,” the Lochner case “notorious.” His approval of Jim Crow laws is held against him. Peckhams’s extremely conservative thinking does not resonate with modern sensibilities.

The demise of High Point Farm

When the two Peckham sons were grown, each became a lawyer. Harry had developed a deep love of the land and a genuine interest in agriculture. Even though he was active in his father’s Albany law firm, he purchased a farm on the same ridge as Coolmore to the east of his father’s property which he named “High Point Farm.”

Registered stock including bulls, cows, pigs, geese, duck, and turkeys — some imported — found a home at this farm. Running a serious agricultural operation, Harry commuted out of Albany to work on his beloved High Point Farm whenever he had the opportunity and employed several hired farm workers.

Ads appeared in The Enterprise during 1899 and 1900 with the offer that for a dollar local farmers could have their cows serviced by one of his pedigreed bulls. Pigs and poultry were also for sale.

Unfortunately, a disastrous fire broke out in June 1900 when the hay barn, stables, wagon and tool house, pig pen and other buildings, equipment and much stock were all destroyed. Harry did not rebuild because by this time his health had begun to fail.

Sadly, Harry seemed to have developed consumption, now known as tuberculosis, a disease that in those days was fatal to rich as well as poor. He moved to Saranac Lake, then a center for treatment, later relocating to the west in a desperate attempt to revive his health. Harry died in 1907 in California. His brokenhearted parents had already buried Rufus Jr., also a promising young lawyer who had died at Coolmore after a lengthy illness in 1899.

Mourned by the president

As usual, Justice Peckham returned to Coolmore for the summer of 1909. Despite his health being a cause for concern, he was planning to return to Washington in the fall. However, his heart failed and he died at the summer home he had visited for a quarter of a century. At his death, tributes and messages of sympathy poured in.

Justice John Marshall Harlan referred to him as “one of the ablest jurists who ever sat on the American bench.” President William Howard Taft and Governor Charles Evans Hughes (who the next year became an associate justice himself and later the chief justice of the Supreme Court) each sent his widow their condolences.

At his impressive funeral at Albany’s St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, the eight surviving Supreme Court justices were in attendance. Rufus Wheeler Peckham was interred in the family plot at Albany Rural Cemetery.

Locally, Peckham has been almost entirely forgotten, though he was once the most important of the area’s summer residents. The Peckhams must have loved their summer home, which remained in the family from 1884 until Justice Peckham’s death there in 1909.

In the early 1920s, the estate came into the possession of the Cobb family who renamed the property “Woodlands.” In 1958, after Bernard Cobb’s death, his daughters donated the 32-room house and 40-acre tract of land to the Albany Catholic Diocese.

Location:

— United States National Archives and Records

“Dreadful scenes”: In the midst of the Meuse-Argonne Forest Offensive, Major Frank H. Hurst was gassed with phosgene, a compound of carbon monoxide and chlorine, and was carried on a stretcher to a base hospital. This Department of Defense photograph shows a gun crew from Regimental Headquarters Company, 23rd Infantry, firing during an advance against German entrenched positions at Meuse-Argonne.

— United States National Archives and Records

“Dr. F.H. Hurst Is In Thick of the Fighting” was the Altamont Enterprise headline, describing the Guilderland Center doctor helping the wounded in September 1918 after the Battle of St. Mihiel. Hurst in August had been transferred from a British regiment to the American Expeditionary Forces. This Army photograph shows the American Engineers returning from the front at St. Mihiel.

Dr. Frank H. Hurst was a Guilderland Center boy who became a doctor, graduating from Albany Medical College in 1895, followed by two years in Europe where he continued his medical studies. Returning home, he opened his practice in Guilderland Center in 1903 and served as the community’s physician until 1945, except for the years from 1917 to 1919.

August 1914 saw the opening shots of catastrophic World War I in Europe, a war that resulted in millions of casualties, a war in which the United States wanted no involvement. The nation adopted the official policy of neutrality.

When the Germans, who began unrestricted submarine warfare to prevent food supplies and war materiel from reaching Britain, started sinking American merchant ships in early 1917, the United States declared war on April 6. Having only a small regular army and an inadequate medical corps, the nation was ill prepared for all-out war. Many volunteers immediately came forward, including 44-year-old Dr. Hurst.

An early June Enterprise announcement informed everyone Dr. Hurst was leaving that day for Ft. Washington in D.C. where he would become part of the medical corps of the regular army, having been given the rank of lieutenant weeks before. Six weeks later, readers were assured the newly promoted Captain Hurst had reached France safely.

“Dr. Hurst Writes” was a front-page feature in early November 1917, penned in response to an Enterprise request to his wife for information. In a very lengthy letter written directly to the newspaper, Dr. Hurst gave details of his early months in service.

His Atlantic voyage had been uneventful under beautiful weather aboard an ocean liner he couldn’t name due to wartime censorship in a convoy protected by American and British destroyers. Upon landing at a British port he couldn’t name, he took a train to London where his accommodations at the “fashionable Hotel Curzon” in a posh neighborhood were provided by the British.

Free for the next few days, Hurst took the opportunity to “visit haunts of his medical school days” as well as doing considerable sightseeing, all described in detail in his letter.

At week’s end, when his orders came through to report to ------------ (because of censorship, lines replaced specific information) in France, he boarded a troop train to ----------, a seaport on the south coast of England where they embarked on a troop ship. After a very rough voyage across the stormy English Channel when half of the 1,300 men on board were seasick, they landed at ------------, a French seaport.

Dr. Hurst had a few leisurely days for sightseeing and a swim in the ocean at a nearby beach. During that time, the fresh troops were being taught how to wear the protective “tin hat” (Dr. Hurst’s quotes), the helmet worn by British soldiers, and how to wear the gas mask so crucial against German poison gas attacks.

Dr. Hurst, although a captain in the American Expeditionary Force, was assigned to a British regiment and would serve with the British until the summer of 1918 when he was reassigned to an American unit. This came about because, immediately after the Americans declared war, the British sent over the Balfour Mission seeking aid, including at least 1,000 doctors.

In a mutual agreement, Dr. Hurst was one of the American doctors and other medical personnel who would be aiding the British in dealing with mass casualties by filling out their depleted medical corps while at the same time learning from British experience in treating the wounded.

His lengthy letter continued that, after being assigned to a unit, they were loaded on a troop train moving only at night, everything darkened; otherwise German planes would have bombed them. Met by automobile, he was driven to headquarters of the 4th Cavalry Division of the Third Army where he was met by “fine British officers” who were “gentlemen,” fed a big breakfast and enjoyed an after-breakfast smoke.

At first, Dr. Hurst was assigned as the medical officer of the Division Advanced Supply Column, then, after several weeks, he was transferred to a British Field Hospital in charge of six wards and given his own operating room. His promotion to captain had come at this time.

Soon after the 1914 outbreak of the war, the Western front became a stalemate between the British and French against the Germans. Each side dug miles of deep trenches through Belgium and France with a no man’s land between them, the trenches protected by rolls of barbed wire.

For long periods of time, soldiers lived in these trenches often in terrible conditions. The strategy of generals on both sides was to initiate attacks with huge artillery bombardments of the enemy, followed by ordering the men out of the trenches to race across no man’s land through the barbed wire to attack the entrenched enemy in the face of machine gun fire, shrapnel, and after 1915 poison gas.

Casualty rates were catastrophic and by war’s end the British alone counted 487,994 dead. In his references to actual combat Captain Hurst (for the remainder of the war, this is how he signed his letters) refers to “carnage” and “roar of the battle,” additionally mentioning the constant strain from the danger of shrapnel, bombs, shot and shell, and poison gas.

Because his hospital was near an aerodrome, Captain Hurst often treated aviators who were sick or wounded, making friends with many of them. He didn’t hesitate when offered the opportunity to fly numerous times, once to the altitude of 16,500 feet, which he noted in his letter was about the distance from Guilderland Center to Altamont. He claimed the sight of the sky when flying above the clouds was “one of the finest experiences of my life.”

After time on the front line, he was given leave, and always the intrepid sightseer, he visited Paris and Rouen, observing that almost every woman whom he saw was dressed in mourning. He did admit that sleeping in a real bed and enjoying a real hot tub bath was deeply appreciated.

Captain Hurst’s letter ended with his address, giving the folks at home the opportunity to write the latest hometown news. His letter was actually the length of a magazine article, not what you would ordinarily think of as a letter.

New year in a wasteland

The next of his published letters was written soon after New Year’s Day in 1918 to the Guilderland Center Red Cross branch that he had helped to establish before he shipped out, leaving his wife in charge for the duration of the war. Appearing in the Jan. 11, 1918 edition of The Altamont Enterprise, the letter came from “somewhere in France.”

He thanked Enterprise readers for their Christmas greetings, giving assurances he had read and reread them. After characterizing the Germans as “ruthless” and “insidious,” he let the Red Cross members know how much the troops appreciated the items that had been sent over to them.

Describing the devastated countryside as being in complete ruin, there were few comforts for the troops in the trenches, “just the bare necessities of coarse food, scant shelter from the elements and only enough fire to keep from actually suffering in the wintery atmosphere and when in actual fighting not even that.”

While giving no specifics of the recent fighting on the front lines, he let his correspondents know by telling them if they had followed the activities of the cavalry from Nov. 19 to Dec. 6, they could get an idea of his surroundings.

Those who followed the war news would realize that it had been the Battle of Cambrai in France where the British Third Army bombarded the enemy’s Hindenburg Line firing 1,000 pieces of artillery, and then had ordered thousands of men and 476 tanks to attack the Germans along a five mile front. There had been huge losses on each side with little gain.

Captain Hurst’s dedication to the cause was clear when he wrote, “I am not complaining, for before I offered myself for the common cause, I knew full well all the privations and hardships and suffering that were before me.”

Brush with death

March 1918 saw a note in The Enterprise that Captain Hurst, while with the British army 10 miles back from the firing line, had had a close brush with death, when just after dismounting his horse, as he turned to speak to someone, a shot killed the horse.

Also recently he had been under fire on the front line when tending to a wounded soldier in a shell crater where he was trapped from early morning until after dark when he was able to crawl through the mud back to British lines.

The front page headline of May 3 read, “United States Medical Unit Was Captured,” “Captain Frank H. Hurst of Guilderland Center Says Only Self and Major Escaped Somme Fight — Was Wounded in The Hand.”

Mrs. Hurst had notified the editor that Dr. Hurst and the major were the only two in their medical unit who weren’t killed or captured. He was wounded in the hand while evacuating wounded under shell fire on March 23 and by the 24th all had been captured or killed except himself and a major.

This attack was part of General Erich Ludendorff’s huge offensive to reach the English Channel by breaking out between the British and French armies. At first, the Germans successfully managed to push the British back 12 miles, hence the need to evacuate British wounded from the onslaught of the Germans. The German strategy was unsuccessful and their desperate attempt failed.

Soon after the offensive came to an end, Captain Hurst wrote to Mr. and Mrs. John Scrafford in Altamont on April 6, thanking them for cookies he had received the day before after having been without mail for 16 days dues to the German attack. Cookies were a real treat after all those days of eating nothing but hard tack and corned beef.

With an apology for writing the letter in pencil, Captain Hurst explained, “Please excuse my using pencil, for I cannot hold a pen, having been wounded in my right hand by a piece of bursting shrapnel, as we were evacuating our patients while under fire from the enemy as he was advancing on_____________, where our hospital was located. We were under fire the entire time, and as I was directing the loading of patients in next to the last car, a shrapnel burst just as my side, and one piece hit me.

“It is fortunate it was no worse. I held my wound with my left hand until I had finished loading, then jumped on the last car, and as we drove away, I applied First-Aid Dressing to myself and it was 10 o’clock at night, after we had all our patients under canvas on stretchers, that I found time to go to a CCS [Casualty Clearing Station] near our new camp to have my wound treated. But we had saved all our patients. Next morning we had to evacuate again as the enemy was still advancing, and my Colonel sent me to No.2 Stationary Hospital.”

After five days in the hospital, Captain Hurst requested he be sent back to his unit and was happy to report the Germans were being pushed back.

Joining other Americans

Captain Hurst was finally transferred to the American Expeditionary Forces in a different part of France in August 1918. His wife assured the Enterprise editor that her husband was pleased to be with American troops.

“Dr. F.H. Hurst Is In Thick of the Fighting” was the headline describing another letter shared by Mrs. Hurst. Writing in mid-September, he had been reassigned to the 89th Division’s 314th sanitary train, after having first been ordered to the 2nd Cavalry to “get their medical equipment in shape.”

Explaining that the 314th sanitary train corresponded to the field ambulance he had been attached to with the British, Captain Hurst went on to relate his first experience of battle with American troops.

Amazingly, he was writing on “Boche” paper left behind in the German field hospital his division had just captured, following “so closely on their heels that they left practically everything — even the water was hot on the stove in the sterilizer.”

The 89th had been part of the American army’s advance and capture of the St. Mihiel salient, a bulge in the German line held for four years of German occupation. This offensive from Sept. 12 to 16 was the first for the green American soldiers involved.

Captain Hurst’s wife was told not to worry about him if he didn’t communicate for a time, he was so busy dressing wounded that he barely had time or eat or snatch a little nap, noting, “I have been in the thick of it.” He had had no mail and hoped to send this letter out with an ambulance driver. He claimed to be well, and feeling fine, only very tired.

Captain Hurst sent a second letter a few days later, this time on a German officer’s stationery, unsure if she had received his earlier letter. He was terribly upset that, while he and others were fighting in the St. Mihiel offensive, thieves had entered the barracks they left behind and had ransacked it.

“I have lost my trunk and all my souvenirs and postcards, as well as my two good and almost new uniforms, everything I had except my old uniform I had on last spring when I was in the British retreat,” wrote Captain Hurst.

He also complained of losing his shaving kit and bedding roll. However, his most regretted loss was his diary. The two letters appeared in the Oct. 25, 1918 edition of The Enterprise.

Within a month, the 89th Division was relocated to the Verdun sector where they were heavily engaged in the Meuse-Argonne Forest Offensive, one of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s efforts to force the Germans to retreat from their defensive Hindenburg Line. Combining forces, the United States and France threw in 37 divisions but, while the Germans were pushed back, their line held and no breakthrough was achieved.

Major Hurst is gassed

In the midst of this battle, Major Hurst was gassed by phosgene, a compound of carbon monoxide and chlorine, and was carried on a stretcher to a base hospital where he lay for three weeks.

“Major Frank H. Hurst of Guilderland Center Tells How He Was Gassed” was the headline in the Dec. 13 Enterprise, updating readers about his promotion in rank and his latest news from the battlefield.

Unable to lift his head from the pillow for three weeks, and overcome with faintness if he tried, his heart had been weakened from the effects of the gas. According to his doctors, it would be a month before he would feel stronger.

Having been wounded twice previously, Major Hurst commented, “Nothing compared to this, the Huns nearly got me this time.”

His letter says that he had actually been gassed twice, the first time light enough to keep tending the wounded, but the second time weakness overcame him and hemorrhaging began from his lungs. Now that he was in a hospital bed away from the sound of guns, the quiet came as a relief after having been in constant warfare for over a month.

A second letter penned a few days later was also included in the paper. Now reporting much improvement, he was now able to sit up in a wheelchair, but was not yet allowed to walk.

As soon as his heart was stronger, he was going to be transferred to Cannes on the Mediterranean for further recuperation. As it was, the current hospital’s location was peaceful and beautifully located, one of 10 hospitals 40 miles from Dijon able to accommodate 20,000 patients.

A letter written Nov. 1 brought news that Major Hurst had walked the length of the ward, gaining strength so rapidly that, by the following day, he had walked around the pavilion outside. He expressed a wish that peace would come.

Armistice brings joy

The Armistice ending the fighting was to take effect at 11 a.m. — the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month: Nov. 11, 1918.

In Major Hurst’s next letter, written 11 days after the armistice had been signed and peace had come to the trenches, his expression of relief was obvious. “When I am well again,” he wrote, “I will not have to go back to those dreadful scenes.”

He followed this with a description of the rejoicing following news of the armistice in the nearby small village of Allavey, where there were parades and flags, singing and shouting, guns being fired off from the fort on the nearby mountain and from ships in the harbor while ecstatic Frenchmen shook hands and the women, weeping tears of joy, handed out flowers and kissed them, all in gratitude for American aid in winning the war.

The celebration went on far into the night. Now that he was in Cannes in southern France, Major Hurst felt the balmy climate was restoring his health. The time spent on the beach under the palm trees or sailing and fishing with other officers was just what was needed.

Early in January 1919, orders had come through for Major Hurst to report to the commanding general at Bordeaux who ordered him to take command of the 500-bed Camp Hospital No. 79, situated in a beautiful 600-year-old chateaux at St. Andre de Cuzal. He was feeling well, but still coughing at night, fearing it would be some time before embarkation home.

His next letter, written on Easter morning, mentioned his disappointment at not being sent home and discharged in spite of putting in for it, but he was hoping he’d be home by July or August.

He proudly related that, “General Noble, the Commanding General here at Bordeaux, told me I have established the finest hospital — large or small — that he’d seen in France, and he wants me to keep charge of it. We take care of the boys who are taken sick while here in the area awaiting embarkation; we get them in shape and well, to send them home to their people healthy.”

Finally released from active duty, Major Hurst sailed on the liner Saxonia, leaving Brest for the United States and finally reaching American shores in July. After getting his final discharge, he resumed his medical practice in the Guilderland Center area immediately.

However, his military career wasn’t over quite yet. In early January 1920, it was announced that he had been promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in recognition of his faithful and distinguished work for medical services while in the war zone. He then served in the Army Medical Corps Reserve and during the next few years periodically reported for duty. He finally retired from the reserves in 1925.

Location:

“Hank Apple’s tap” was immortalized by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft in his Anti-Rent War narrative poem “Helderbergia” when he has innkeeper Apple “replace the feast, while gin its reign resumes.”

The local men, travelers, and drovers frequenting one of Guilderland’s many late 18th- or early 19th-century taverns did imbibe gin, brandy, rum, and whiskey. However, it was also very likely that cheap, locally-made hard cider or applejack flowed from the “taps.”

An 1814 bar book from the Severson Tavern, once located at the base of the Helderberg escarpment in what is now Altamont, recorded that Wm. Truax owed 9 pence for 1½ mugs of cider; Lot Hurst drank 1½ mugs of cider at a cost of 9¼ cts.; Jacob Zimmer spent 18¾ cts. for 3 mugs of cider; and Evert Barkley downed 1 cider eggnog, an extravagance of 12½ cts.

The drink of choice among all age groups during these years, cider was widely produced by local farmers from the plentiful apple trees thriving in Guilderland and wherever farmers had settled in New York State. Although Esopus Spitzenburgs, Northern Spy, Yellow Newtown, and Lady Sweet were among the apple varieties that could be found at that time in the state, most early farmers had little concern about named varieties or their apples’ attractive appearance as long as the trees on their farms produced flavorful fruit.

During these early year,s most apples not eaten fresh were crushed into cider by family members or they dried slices chiefly for their own use. However, sometimes they bartered these for goods or services.

According to John Winne’s account book of 1810-1818 recording the transactions of his Dunnsville store and tavern, local families could barter one bushel of dried apples for $1.50 worth of merchandise at his store or one barrel of cider for the value of $1.00. A day’s labor for Winne earned only $.50 credit, illustrating the economic importance of apples at that time.

Knowersville’s Dr. Frederick Crounse was willing to accept a barrel of cider in exchange of $1.50 worth of medical treatment and for that price would “excise a tumor.”

The cider those hardy folks drank was not the pasteurized stuff we drink today. In those days, the sugar content of the pressed apple juice rapidly fermented, creating the low alcohol content of “hard cider.”

The hard cider could further be distilled into potent apple brandy or applejack. Old timers could put out a pail of hard cider on a bitterly cold winter’s night and, come morning, the water content would be frozen, leaving a small amount of highly alcoholic applejack.

Later in the 19th and early 20th centuries, local farmers could make their families’ cider supply with inexpensive cider mills such as “The Little Giant Cider Mill” for $7.65 that could be ordered from the 1897 Sears, Roebuck Catalog. Or they could buy a barrel of cider already pressed from W. D. Frederick for $2.88 as noted in his 1888 account book or at other cider mills in the area.

Another product of cider was vinegar. In the 1880s, A.V. Mynderse was a “manufacturer of and wholesale and retail dealer in cider and vinegar” in Guilderland Center.

Cider and vinegar producers advertised in The Enterprise, urging farmers to bring in their apples at what were much lower prices than for high-quality fruit. However, for drops or a farmer with only a few trees, it was a way to earn ready cash even if the price per bushel was under $1.

During the last years of the 19th Century, larger scale apple production had turned into an important source of cash income for town farmers. Paying calls at local farms, out-of-town buyers sought good quality fruit to be shipped out by rail to big-city markets.

One year, Fullers farmers were visited by a Utica buyer purchasing apples to be sent to Philadelphia. A.M. LaGrange, a farmer living in that part of town, sold 100 barrels in 1889. He had “the reputation of growing some of the finest apples in this locality.”

Each of the town’s four railroad depots were the scenes of the departure of carloads of apples destined for East Coast cities. Reporting from Guilderland Center in 1901, “The first installment of apples purchased here…was shipped from this station to New York last Saturday.”

Prices for either grade of apples varied, depending on scarcity and demand. In 1892, farmers received $2.25 for a bushel of fine quality apples, but it was unusual to receive that much per bushel. In 1896, The Enterprise noted, “Apples are cheaper this year than ever before in our recollection, prices ranging from $.50 to $.75 per barrel for nice choice fruit.”

After 1890, area apple-growing farmers found a steady market for their apple crop when Charles H. Burton and A. Elmer Cory of Albany opened up a cider and vinegar manufacturing plant near the D&H tracks in Voorheesville capable of crushing 9,000 pounds of apples daily. Named the Empire Cider and Vinegar Company in 1891, it was eventually known as Duffy-Mott.

It was an immediate success and, within a year after opening, several 1,000-gallon tanks were added to the operation. Advertisements in The Altamont Enterprise urged farmers to bring their apples to the Fullers and Altamont railroad stations for shipment to the new processing plant.

By 1900, three-thousand bushels were pressed daily during a 70-day season. In later years, apple juice and applesauce were added to the product line. Duffy-Mott closed down the plant in 1955, striking a serious economic blow to farmers who lost a ready market for their apple crops.

At first, the variety of apples didn’t seem to matter much for individual farmers. In 1895, apple trees of no particular variety could be purchased very inexpensively from Jas. Hallenbeck of Altamont when he offered 5½- to 7-foot trees for only $.15 each.

This casual attitude changed as buyers grew increasingly picky about quality. Diseases affecting trees and fruit such as scab and codling moths and by the 1920s the “skeletonizer” disease had appeared, making “arsenical applications” necessary to save the apple crop.

Until the mid-1950s, extensive acreage in and around Guilderland Center was devoted to apple orchards. A wildfire that threatened the drought-stricken hamlet in 1947 succeeded in destroying the 1,000-tree fruit orchard of Edward Griffiths on the western end of the village.

However, a 1950 aerial view of Guilderland Center appearing as part of a Knickerbocker News article revealed row upon row of apple trees on the site where today stand the firehouse, the school bus garage, the high school and its playing fields, and houses — all once owned by A.V. Mynderse, the vinegar-maker.

With the closing of the Duffy-Mott plant and the pressure of development, all of Guilderland’s orchards are gone now except one. Altamont Orchards remains to carry on our town’s apple tradition.

The original orchard was planted by Dr. Daniel H. Cook, a prominent Albany doctor who used the land as his summer home and gentleman’s farm. He was a serious agriculturalist who planted 3,000 apple, pear, and plum trees, considered a very fine orchard in 1899.

In 1967, the Abbruzzese family took over the property, opening up a farmstand in addition to running the orchards. Operating a profitable apple orchard today is a tremendous challenge, requiring the owners to do more than tend the trees.The competition from other states and countries is fierce.

State health regulations control the making of cider, now requiring it to be pasteurized. There is no more amateur hard cider, although professionally produced hard cider has had a revival recently.

Today, in addition to their farm stand and orchard, the Abbruzzese family has established a golf course and restaurant on the property in order to stay in business.

Solely depending on income from an apple orchard is not practical these days for a farmer in Guilderland unless other avenues of profit are explored. The time may come when Guilderland’s apple history is all past history.

Location:

Many decades ago, peals of bells housed in cupolas atop local schoolhouses signaled dawdling children that classes were about to begin. Once standard equipment for old-time schools, most school bells have disappeared along with most of the school buildings where they once hung. Fortunately, a few of Guilderland’s historic school bells have survived.

In 1900, Guilderland’s several common school districts were scattered throughout the town to be within children’s walking distance from home, offering education up through eighth grade.

With district numbers in parenthesis, they were: Settles Hill (1), Dunnsville (2), Parkers Corners (3), Hamlet of Guilderland (4), Wormer School (5), Guilderland Center (6), Altamont (7), Gardner Road School (8), Osborn Corners (9), Cobblestone School on Stone Road (10), McKownville (11), McKownville Annex (11A), Fullers (13), and Fort Hunter Bigsbee School (14).

District 12 had disbanded in the 1890s, followed by the closure of the Wormer School in 1906. By 1902, Altamont had become a Union Free District and had opened its high school.

Early in the 1930s, New York State began to urge rural areas with many small local districts like Guilderland’s to merge into centralized districts, doing away with old-fashioned, one-room schools and offering modern high school education.

In 1941, the Voorheesville schools centralized, including Guilderland districts 5, 8, and 10. That same year, Guilderland Center residents voted to pay tuition, enabling their children to attend Voorheesville schools even though they didn’t become part of that central district.

Eventually, Guilderland’s remaining districts plus North Bethlehem voted to form the Guilderland Central School District in 1950. Once modern Fort Hunter, Altamont, and Westmere elementary schools opened in 1953, the old one-room schools were auctioned off.

Whatever became of the school bells?

Parker Corners bell to inspire modern scholars

Hidden away in a grass-covered courtyard at Guilderland High School rests the bell that once warned the little scholars attending the Parkers Corners District 3 School that classes were about to begin. The three-foot high bronze bell, cast in 1864, is inscribed in raised lettering, “Joy and gladness shall be found therein, Thanksgiving and the voice of melody.”

The bell is 33 inches in diameter and originally called worshippers to the Old State Road Methodist Church. Charles Parker, a wealthy New York City man who lived for a time in the area, donated $4,000 in 1864 to build a Methodist Church near his home. At that time, a church bell was purchased from Jones and Company Bell Foundry of Troy, a foundry in operation from 1852 to 1887. By the late 1930s, the dwindling congregation forced closure of the church.

Nearby on West Old State Road stood the Parkers Corners one-room school where one November morning in 1942 fire erupted just as pupils were arriving. While desks, books, and the adjoining wood shed were saved by neighbors’ immediate action, the building was a total loss.

Realizing that, due to World War II shortages, there was no chance of arranging the transportation of students to another district, residents quickly noted the empty church building in their midst would be the perfect solution. The former church served as the Parkers Corners School until 1953 when students began attending Fort Hunter Elementary School.

After having been sold at auction, the building burned in a suspicious fire, but not before the bell had been removed to be placed by the flagpole near the front of the new Guilderland Junior-Senior High School when it opened in 1954. The bell was to serve as a “symbolic link of the ten former common school districts with the new centralization.” Today, because of the extensive expansion of the high school building over the years, the bell is now in an enclosed courtyard.

Guilderland bell traveled to Greece

The trip from Parkers Corners to the new junior-senior high school was a short one compared to the journey traveled by the bell from the Guilderland District 4 School.

In 1847, the District 4 School became the town’s first two-room school. When the building was remodeled and enlarged in the 1890s, it boasted a “fine” new bell donated by village residents Messrs. Newberry and Chapman, owners of the Guilderland foundry. Because casting bells was such a specialized operation, it is unlikely the bell was cast at their foundry.

After the 1953 opening of Westmere Elementary School, the Willow Street school building served as Guilderland’s first real town hall before becoming a State Police substation.

As Nazi invaders swept through Greece in 1941, they confiscated anything that could be of value to their war effort, including the bell that hung in St. Nicholas Church in the small Macedonian village of Siatista. Communist unrest in that area of Greece during the years immediately following the war prevented the villagers from replacing their cherished bell.

Mrs. F.C. Cargill of Guilderland became aware of the village’s loss and knew that the Society of Siatisteon Siatista, a New York City group of former Siatista village residents, sought a replacement bell. She contacted William D. Borden, president of the Guilderland Board of Education to inquire if one of the district’s old school bells could be donated.

The board quickly approved, giving the bell from the Guilderland District 4 School to the society which took over the responsibility and cost of shipping the bell to Greece. After its arrival, the bishop sent a gracious thank-you for the bell to the board of education saying, “By its sacred tolling it may summon Christians to worship God.”

Dunnsville bell at Town Hall

The Dunnsville District 2 one-room school dated back to 1875 when it replaced an earlier 1820 building. In 1882, a bell cast at the Clinton H. Meneely Bell Company, a Troy bell foundry, was placed in the cupola of the new school where it rang out 15 minutes before classes began, again at class time, and then again at noon.

Viola Crounse Gray, a Dunnsville student in the early 1900s, recalled her father and other local farmers coming in from their chores for their midday meal at the sound of the school’s noon bell. As the last trustee of the school, in 1953 she had the opportunity to purchase any school property not needed by the district.

Sentimentally, she wanted the bell she remembered so fondly from her childhood. In 1982, when she and her husband, Earl Gray, offered the bell to the town, it was placed in front of Town Hall.

Stone Road bell at historic house

Once ringing out from above the Cobblestone District 10 School on Stone Road, today the school’s 320-pound bell rests silently in front of the Mynderse-Frederick House. Because this Guilderland district became part of the Voorheesville Central School District, it isn’t clear when the building ceased being used as a school and became a private residence.

At some point, its bell came into the possession of the Albany Institute of History and Art, later passing into the hands of the Christ Lutheran Church in McKownville. When the bell proved too heavy to place in the church’s bell tower, it languished in a storeroom for 30 years.

Eventually, the church historian got in touch with then-Town Historian Fred Hillenbrand to offer the bell to the town. After Guilderland Highway Department workers refurbished the bell, cast in 1868 at the Meneely Bell Foundry of West Troy (after 1896 renamed City of Watervliet), it was placed in its newest location in front of the Mynderse-Frederick House.

Cobblestone school still has its bell

To have a genuine glimpse of the past, observe the old Cobblestone District 6 School in Guilderland Center with its bell still in its cupola as you drive by on Route 146. The building was erected in 1867 and is still owned by Guilderland Central School District.

During the period of time when these rural schools were built, the cities of the Capital District were manufacturing centers employing countless workers. Among the factories in Troy and West Troy (Watervliet) were bell foundries turning out thousands of bells sold all over the country for schools, churches, and government buildings.

When you pass by the bells at Town Hall or in front of the Mynderse-Frederick House, remember the early system of common-school education they represented as well as the industry that was once so important to this area.

Location:

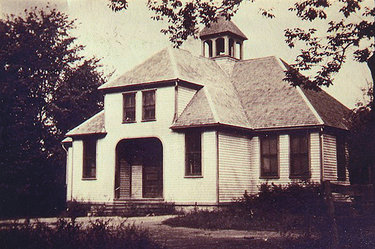

Now an apartment building at 131 Maple Ave. in Altamont, the District 7 common school building, built in 1879, once stood on School Street (now Lincoln Avenue). After the Altamont Free Union School opened in 1902, James Keenholts bought the old school building at auction for $875 and had it moved to Maple Avenue.

America’s advances in technology and the growth of business activities at the opening of the 20th Century made it obvious that educational skills beyond those offered by the traditional eighth-grade common schools, then typical in New York’s rural communities, were needed.

Altamont’s School Street (later renamed Lincoln Avenue) had been the site of District 7 common school since 1879, but by 1901 many in this prosperous and expanding village were questioning the adequacy of the education received there by the village’s youth.

Calling a meeting of taxpayers in early April 1901, school trustees sought a consensus either to repair the current school building or to choose a different site and erect a new one. The trustees had heard complaints about the poor and limited quality of education available in the District 7 common school, often deterring outsiders from settling in the otherwise up-and-coming village and forcing villagers to send their children to board in the city if they wished them to get schooling beyond eighth grade.

The trustees made it clear they had hopes of winning approval for a new building large enough to allow Altamont to eventually become a union free school district permitting a high school department. Uneasy taxpayers were assured that enough non-resident students would attend a high school, paying tuition to defray any additional expenses.

The special meeting brought out a sizable number including a few taxpayers who were no happier at the thought of higher school taxes than taxpayers a century later. One suspicious attendee demanded to know why the meeting had been called.

In answer, one trustee read to the assembled group a letter received from the State Department “calling attention to the deplorable condition of the school building and grounds.” A resolution was made to raise $500 to repair the old school but, when it was pointed out that the meeting was not called according to a state law that mandated school meeting notices could only be issued by a person who is also a taxpayer, the resolution died.

With that, the meeting became an informal gathering where the talk drifted over to the need not only for a modern school building, but a school that would offer more advanced studies than the common school. W.S. Keenholts, one of the school trustees who obviously had come prepared, immediately launched into the requirements that applied to a union free district, legally necessary to establish a high school in New York State.

At that, attendees signed a petition almost unanimously for the trustees to call a second meeting to have an official vote on becoming a union free district. The sentiment seemed clear that Altamont needed a new building offering a higher level of education to keep up with the times.

As the meeting approached when legally eligible voters would decide the question of becoming a union free district, arguments in favor appeared in The Enterprise. “Progressive up-to-date people of the district” not only felt it was a good business proposition, but would give more children the opportunity to get an advanced education.

The old attitude that the eight-grade common school was good enough for my father and good enough for me was “false reasoning.” A comparison between the old common school and the academic department of a union free school made it clear “more extensive book knowledge” was a necessity in “the professional, the industrial, the commercial and the political world” of that day.

The night of the meeting, Mr. Thomas E. Finnegan of the New York State Department of Public Instruction and two other men representing communities that already had become union free districts spoke of the advantages of this type of district.

Advocates of change triumphed when the votes in favor of the new type of district were 124 to 14. A board of education was elected to look into a site and plan for a new building.

By early July 1901, the board of education called a meeting with plans for a new school building and the necessity of raising the sum of $10,200 for construction costs. In addition, $1,800 would be needed for heating and sanitation, and $500 for furnishings in the new building. An additional $800 had to be raised to purchase a two-acre plot on the corner of Grand Street and Fairview Avenue. It was planned to issue bonds to be paid off $1,000 plus interest annually.

The building’s architect was Altamont resident Wilber D. Wright. The notice calling for contractors to submit bids called for an eight-room, two-story school building of solid brick, 50-by-78 feet with a basement. It was to have the capacity for 250 students.

No bid was as low as the figure set by the board of education but, after a way was found to get the additional $3,000, the construction contract was awarded to the lowest bidder, Mr. J.W. Packer of Oneonta.

The old school was auctioned off in 1902 once it was no longer needed, purchased by James Keenholts for $875. Soon after this, he had the building moved over vacant lots to Maple Avenue.

By October 1901, Crannell Brothers, then located in Altamont, had brought in D&H carloads of lumber and Rosendale cement. Work on a foundation of bluestone brought from Fred V. Whipple’s quarry was soon underway.

Many spectators walked over to Grand Street during the next few months to observe the construction progress. Once the exterior was complete, Altamont’s A.J. Manchester installed the heating and plumbing while George T. Weaver put in lathing and plastering. By early summer 1902, the building was completed and formally accepted by the board of education.

The principal of the new school was Professor Arthur Z. Boothby, who had already been hired by the district fresh out of Albany Normal School in 1900. His salary for 1901-02 was $540.40.

Also on the faculty were several women who earned in the $300 range. A janitor had also been hired. The total school budget adopted by the board of education for 1902-03 was $2,495.50.

With the school’s opening imminent, the school board put out publicity, encouraging out-of-town tuition-paying students to attend. Promoting the new school as having “all the latest in equipment in sanitary arrangements and provided with all necessary apparatus for pursuing higher studies,” enrolled students were to be taught by a “competent corps of instructors.”

Tuition rates for non-resident students were given per quarter: academic, $2.50; intermediate, $2.50; and primary, $1.75. For those living along the D&H line, commutation per month was: Delanson, $3.00; Duane, $2.50; Voorheesville, $3.00; and Meadowdale, $2.50. While the costs of construction, personnel, and commutation seem very low, these figures are for 1902 dollars.

A general invitation went out to Altamont’s villagers, urging them to attend the dedication ceremony on Sept. 18, 1902 when the school building would be open for people to wander through. Even though the weather that day turned out to be rainy and unpleasant, a large crowd turned out to participate in opening ceremonies held in the large assembly room.

The program included prayers; scripture readings; and speeches, followed by Dr. Jesse Crounse, president of the Board of Education, who reviewed the rules of the school including one holding the parent or guardian responsible for any damage done by a child to furniture or the building.

School opened Monday with an enrollment of 154 pupils (this number included Altamont’s elementary grades as well) including 10 non-residents. The high school’s first graduating class in 1905 had 11 graduates.

By rights, Altamont residents were extremely proud of their new school, built at great financial cost for such a small village. The school was in use until the centralization of Guilderland’s schools took place in 1950.

By 1953, the new Altamont Elementary School, built on the same plot of land as the old Union Free School, and a year later Guilderland Junior-Senior High School in Guilderland Center were open. The once-modern building in Altamont stood empty.

In December 1955, when it was decided there could be no possible future use for the structure, the board of education of the Guilderland Central School District awarded Jackson Tree Service a contract to demolish and remove the debris of the grand old building for a bid of $3,250.

A New York State Historic Marker stands on Grand Street to indicate where the Altamont Union Free School once stood. It is ironic to think the solidly constructed school was razed, replaced by a lawn and a marker, while the inadequate District 7 common school building is still standing today at 131 Maple Ave. and is now used for residences.

Location:

Without a GPS to route them to Meadowdale, Gardner, or Frederick roads, few current Guilderland residents could find their way to Meadowdale, and once there would wonder: What’s Meadowdale?

Although difficult for us to believe today, a century ago Meadowdale was one of Guilderland’s small hamlets with an identity all its own, reflected in its little weekly column in The Altamont Enterprise.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the locale was an area of scattered farms tenanted by leaseholders of the Van Rensselaer West Manor. With the Helderberg escarpment rising just to the west and the Black Creek meandering through the fertile farmland, it was a very scenic spot.

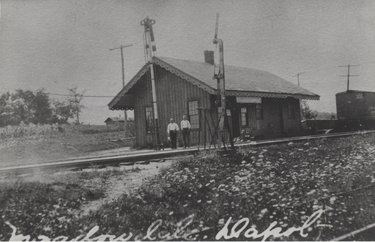

A site was chosen here to become the only stop on the Albany & Susquehanna Railroad between Voorheesville and Knowersville when the railroad laid track through that part of Guilderland in 1863.

Within a year, a small passenger depot and freight office was erected in a location where the tracks crossed a dirt road now called Meadowdale Road; the sign hanging from it identified the stop as Guilderland Station.

A few years later, the A&S Railroad was absorbed by the Delaware & Hudson Railroad. A sizable amount of the D&H’s profits stemmed from summer passenger service: group excursions, day trippers off to a scenic spot, urban vacationers either boarding at country hotels or with farm families who took in summer boarders for extra income.

The logic of D&H executives renaming the stop from its original pedestrian name Guilderland Station to the more attractive sounding Meadowdale is obvious. Annually, the company published the “D&H Directory of Summer Hotels and Boarding Houses” where the prospect of stopping at Meadowdale would certainly seem lots more appealing to prospective visitors.

Each sunny weekend, numerous day trippers came out from Albany to the little depot, planning to hike the two to three miles up the “old road” through Indian Ladder Pass to the top of the escarpment. An Altamont livery stable owner usually would send over one of his wagons to transport for a small fee those who were unable to do the vigorous hike themselves up the escarpment road. At the end of the day, the weary hikers journeyed back to Albany after their day in the country.

Boarding houses on Thompson’s Lake would often send a wagon to pick up expected guests as well. And farmers came by to pick up boarders who were coming to stay a week or more at their farms.

In later years, many Boy Scout troops came to hike up and camp out on top of the escarpment. Local trains were frequent and inexpensive with a 1909 timetable listing fares with the price of a round-trip ticket from Albany to Meadowdale 79 cents while one way was 42 cents.

By 1900, the area around the little depot had become a much bigger railroad complex with a water tower across the tracks, a necessity in those days of steam locomotives. Nearby was a utility shed for storage of track maintenance equipment and across the tracks from the depot was a freight yard where numerous freight cars that brought up coal from Pennsylvania mines could be parked until the fuel was needed to feed the fire boxes of D&H locomotives.

For many years, large quantities of hay was shipped out of Meadowdale, a major profit-making crop for local farmers during those horse-drawn years.

In the 1886 Howell & Tenney History of Albany County, the name is still given as Guilderland Station, characterized as “a hamlet of about 100 people,” with two dealers in cut hay, a blacksmith and a “general merchant.”

A few years later, in 1897, when Landmarks of Albany County was published, rather confusingly Guilderland Station get a one-line paragraph saying it was a small hamlet with no post office with a second one-line paragraph following, mentioning Meadow Dale as a hamlet with a post office in the “extreme southern part of town” — strange since both the store and the postmaster who ran the post office in his own home were only a few hundred feet from the depot.

Soon after the opening of the depot, a Guilderland Station post office was established there in August 1864 and renamed Meadowdale in 1887. While at first the post office was actually in the railroad station, it was later either in the postmaster’s house or more commonly in the community’s general store.

Most of the mail was generated by summer visitors who hiked up the escarpment or were boarding with local farmers. The photograph of the railroad depot appeared on an early 20th Century postcard, one of many sent out with a Meadowdale postmark, though most were of scenes of the Indian Ladder Road or from atop the escarpment.

The general store, for many years run by William Schoolcraft and his wife, not only served folks as the post office, for groceries and other farm necessities, but also as a gathering place to exchange news and gossip. Schoolcraft traveled the area from Voorheesville to Altamont, selling groceries and picking up fresh produce.

School-age children trekked to Gardner Road to the District No. 8 one-room schoolhouse built in 1885 to replace an earlier building. The schoolhouse was not only used for education, but often hosted Sunday afternoon religious services and served as the meeting place for a Christian Endeavor group as well.

A little record book exists labeled “Meadowdale Union Bible School list of membership 1910 – 1912.” No church was ever built in Meadowdale, and probably most people had membership in either an Altamont or Guilderland Center church, but in the horse-and-buggy era, especially in bad weather, it wasn’t feasible to go that far.

In spite of the population being spread out on farms, having the general store on one road, the schoolhouse on another, and no real center to Meadowdale, the people who lived there definitely identified as being from Meadowdale. The little Meadowdale column that appeared with regularity in The Enterprise listed the births, illnesses and deaths, farm news, social events, and endless visits back and forth.

The appearance of the automobile and the rapid growth of travel by car spelled the end of Meadowdale’s prosperity and identity. People no longer rode the train to board with local farmers or to walk up to Thacher Park as the area atop the escarpment had become by that time.

No longer having a market for hay, farmers had to switch to dairy farming or raising chickens or get out of farming entirely. Meadowdale’s store became obsolete once a short drive to Altamont’s A&P or Grand Union markets became possible. During the mid-1920s, the building that once housed the general store was dismantled and reconstructed in Voorheesville.

In 1925, the D&H Railroad, facing a major decline in profits from passenger travel, went before the New York State Public Service Commission, claiming the year before the revenue generated by the Meadowdale station was $1,424.15 while pay for the station agent there cost them $1,779.03.

In 1924, there were only 17 freight cars forwarded and one received because area agricultural production was declining. The D&H’s chief engineer presented the information that there were only six dwellings and a combination store and dwelling with a graveled road (Meadowdale Road) running through.

Seven residents appeared to protest removing the station agent and only opening the station when a train was expected, but the Public Service Commission granted the D&H’s request.

By 1931, passenger trains no longer stopped in Meadowdale and shortly after the station was taken down and the utility building moved down Meadowdale Road a short distance for someone else’s use. Today there is no trace of the station, water tower, or rail yards, though a single track still cuts across Gardner and Meadowdale roads.

In 1926, the post office was closed and residents began to receive mail delivered by Rural Free Delivery to their mail boxes. The one-room District No. 8 School educated the local children for many years, eventually becoming part of the Voorheesville Central School District.

Farmers continued to hang on in the Meadowdale area, struggling with the changes and competition in farming and the challenge of surviving the 1930s Depression.

May Crounse Kinney, written about by Melissa Hale-Spencer in The Altamont Enterprise, grew up in the Gardner Road area, attending the District No. 8 Gardner Road School until she was 14. She married local farmer Solen Kinney, farming his Gardner Road farm with him until 1949.

Her description of working 365 days a year, running her house and helping with the heavy work on the farm, planting harvesting, getting firewood, caring for animals as well as putting up 300 jars of fruit and vegetables, churning butter and sewing clothes illustrated the lives of Meadowdale farmers and their wives during the early decades of the 20th Century.

All this without electricity or telephone service until the 1940s. The first electrical lines were run out to the Meadowdale area only in 1936 by New York Power and Light Corp.

The Kinneys gave up farming when the price of newer farm machinery cost more than they could possibly afford, which is the story of most of the farmers in our area.

Today, you can drive along Meadowdale, Gardner, and Frederick roads and still see the old farmhouses and cross the railroad tracks, but Meadowdale as a community exists only in memory.

Location:

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The adult craze for wheeling came to an abrupt end when the first automobiles began rolling into towns and chugging out past the farms on country roads. This postcard view of Altamont’s Lainhart block tells the story. After that time, bicycles were for children. The Lainhart block, on Maple Avenue, not far from Main Street, burned in the late 20th Century; a public parking lot fills the space today.

One September weekend in the mid-1890s found Fred DeGraff of Guilderland Hamlet and four friends mounting their wheels, pedaling over to Pittstown to visit a friend while, on another I.K. Stafford, Fred Keenholts and Andrew Oliver traveled from Altamont to New Jersey to Asbury Park for an extensive cycle tour.

They reported to The Enterprise, “The wheeling in New Jersey was very fine.” As interest and participation in cycling spread, The Enterprise was abuzz with local bicycle news during the decade of the 1890s, often called the Golden Age of the Bicycle.

This craze for wheels, as bicycles were then commonly called, took off in the 1890s as the technological advances of the previous decade came together to create a practical modern bicycle. It began with the concept of two spoked wheels of equal size on a tubular frame followed by the invention of pneumatic tires to provide a smoother ride and propulsion from pedals connected to a chain driven sprocket.

However, early braking systems were less than adequate until the invention of the coaster brake in 1898. Wheels didn’t come cheap, ranging from $25 for a used bicycle in the mid-1890s to over $100 for the finest models in 1890s’ dollars, a luxury for most people at that time.

Advertisements of bicycles for sale showed up in The Enterprise as early as 1890, some inserted by the manufacturers themselves. Monarch Cycle Co.’s appeared frequently, claiming theirs was “absolutely the best” with elegant designs and unsurpassed workmanship using the finest materials.

H.A. Lozier & Co. not only bragged about the Cleveland bicycle’s construction, but added the practical information that its “resilient” tire could be repaired “quicker and easier than any other tire in the market.” Several Albany dealers jumped into the market and, sensing a good business opportunity, some Altamont men began selling wheels and advertising their wares in the paper as well.

“Notes From Gotham,” a July 1893 Enterprise front-page column, noted there was “a growing interest in bicycling as an amusement,” claiming that there was “a popular craze” for the sport, “destined to be the most popular form of outdoor entertainment that has ever engaged the American people.”

While bicycle owners could be found in all parts of Guilderland, by far most cyclists seemed to be concentrated in Altamont, so many that in 1893 sixteen men joined together to organize “The Altamont Wheelmen.” After electing officers headed by I.K. Stafford, plans were made to find club rooms.

Soon they moved into “commodious” and “airy” rooms on the second floor of J.S. Secors new warehouse where a new coal stove supplied not only heat but hot water for the bathtub they installed! It was claimed that they had a “very cozy room and it makes a pleasant place to spend one’s evenings, if they must be spent from home.” A year later for reasons not given, they moved to space over the post office

Immediately after the club’s formation, its members began planning runs to Amsterdam, Albany via Voorheesville, Guilderland Center, Averill Park, South Bethlehem, Slingerlands, and Sloan’s (now Guilderland Hamlet). Remembering the dirt roads of that time, this was an ambitious undertaking but reports in the ensuing weeks indicate that they really did pedal their wheels to these destinations.

As 1894 came to a close, 36 men had been voted into membership, especially once it was made known that actually being a wheelman wasn’t a requirement to becoming a member. The Wheelmen had become not only a cycle club, but a male social club as well.

At the last meeting of 1894, members were treated to an oyster supper, followed by “soft drinks” and cigars, all this hosted for the 25 men present by the club’s president I.K. Stafford and Altamont bicycle dealer Fred Keenholts.

Another dinner the next year mentions an “elaborate spread, merriment and good cheer.” Another type of social function were “smokers” where the men entertained themselves with reminiscences of the past season’s cycling “through columns of smoke.”

“Bicycle Notes,” a sporadic column appearing in The Enterprise, related the latest bicycle chatter from around town, including the names of those who had recently purchased a new or used bicycle. Abe Tygert got a high-grade Niagara while Andrew Ostrander purchased a 22-pound Relay — those were just two of the many proud owners identified over the decade.

If used, the previous owner’s name was also listed: “Lucius Frederick is the possessor of a wheel, having purchased the one ridden by Aaron Oliver last season, and Chas. Stevell who now rides the wheel which J. Van Benscoten rode during 1894.”

Ladies, too

Appearance and manners were topics once touched on in “Bicycle Notes” when the writer, pleased that more riders were sitting upright, described any rider as “silly” to “hump” himself over the handlebars unless racing. And ladies should always sit upright so as not to “stoop in the slightest degree.”

Noting that pedestrians had the right of way, cyclists were to respect them and, in addition, to avoid running down children and old people. His parting comment was, “There are all sorts of road hogs in the world and it is regretted some of them ride bicycles … Young boys and fresh young men are the greatest offenders.”

A rumor appeared in “Bicycle Notes” that some of the ladies were learning to ride and soon their names began to show up in print. Miss Blanche Warner’s wheel was a “handsome new Remington,” while Miss J. Libbie Osborn chose an Erie. Herbert Winne finally bought a used bike to enable him to accompany his wife, the experienced rider of the family. Unlike the men, women were never mentioned riding any distance from home.

Risky business

Racing appealed greatly to younger, athletic riders and quickly became a popular local spectator sport with the racetrack at the fairgrounds the perfect venue for competition. Independence Day, the Altamont Hose Company’s Field Day and Clam Bake, and the Altamont Fair itself all became occasions for bicycle races.

Prizes were given in cash, objects such as a $5 clock or certificates for merchandise at Albany stores. Often local wheelmen traveled out of town to participate in races. Pity Lew Hart who lost count of the number of laps in a Cobleskill race and missed being one of the winners.

Being a wheelman was a risky business due to inadequate brakes; locally hilly, rutted roads; and in some cases the riders’ own inexperience. One time at the fairgrounds, three entrants tangled during a race resulting in bruises and badly mangled bicycles. During another race, Elias Stafford had his ego rather than his body bruised after a spill at the race track when the paper commented the next week, “The spectacle was too ludicrous for anything.”

Guilderland Center resident John Stewart took a bad spill on the curvy hill at Frenchs Hollow, but the most tragic accident befell an Albany man out riding with James Keenholts near Altamont. He was seriously injured after losing control as he turned his wheel, going down off a bridge near Altamont onto some rocks below.

After Dr. Barton tended to his obvious injuries, he was helped to board the evening train heading to Albany. “It is feared he is hurt internally” was the comment in the next week’s Enterprise.

L.A.W. and order

The League of American Wheelmen, an organization promoting cycling and good roads, had been formed in the 1880s. So many Americans were swept up in the bicycle craze that by 1898 membership in L.A.W. topped 102,000 including some of the Altamont Wheelmen. I.K. Stafford, one of the founders and president of the Altamont Wheelmen, became sanctioned by L.A.W. to officiate bicycle races, which he did at the Altamont Fair for many, many years.

Long before automobiles were traveling the nation’s highways, L.A.W. began to press for improved roads for cyclists, preferably paved. Locally, there was a call for cycle paths, at that time more commonly called sidepaths.

By 1898, pressure from wheelmen forced the Albany County Board of Supervisors to create a County Sidepath Commission. Routes out of Albany were being considered and of course, a route to Altamont through Guilderland Hamlet and Guilderland Center was hoped for by residents here.

A sidepath went out as far as Albany Country Club (now the University at Albany campus) east of McKownville with William Witbeck extending it west as far as his tavern (site of present day Burger King), but it never went beyond that, although sidepaths were laid out from Albany to Schenectady and from Albany to Slingerlands.

The Enterprise reported the discovery that, not only did the cyclists like the sidepaths, but pedestrians found “that it makes a very desirable walk.” In 1902, it was reported the Albany County Sidepath Commission had spent $5,000 building new paths and repairing old ones. License badges — “same price as last year” — had to be attached to bicycles.

Wheeling was difficult enough over the poor country roads, but the lack of signs made finding your way, once out of your own immediate area, maddening. By 1896, The Enterprise demanded that “sign boards should be erected at every crossroad in the town” for travelers and especially the many out-of-town cyclists who passed through.

Within a few months, it was announced that L.A.W. would begin placing in all parts of the state blue metal road signs with raised yellow lettering that would identify the village or hamlet and give the distance to the next one.

As is typical of developments in American technology, prices of wheels came down, the market became saturated, owning a bicycle was no longer so fashionable, and a new technology had arrived to take the bicycle’s place. If he felt there was nothing “to be compared with the exhilarating excitement in riding a light running and responsive wheel,” wait until the wheelman had his first automobile ride!

Within a few years membership fell so low that L.A.W. and the Altamont Wheelmen were disbanded and bicycles were relegated to children.

Location:

One September weekend in the mid-1890s found Fred DeGraff of Guilderland Hamlet and four friends mounting their wheels, pedaling over to Pittstown to visit a friend while, on another I.K. Stafford, Fred Keenholts and Andrew Oliver traveled from Altamont to New Jersey to Asbury Park for an extensive cycle tour.

They reported to The Enterprise, “The wheeling in New Jersey was very fine.” As interest and participation in cycling spread, The Enterprise was abuzz with local bicycle news during the decade of the 1890s, often called the Golden Age of the Bicycle.

This craze for wheels, as bicycles were then commonly called, took off in the 1890s as the technological advances of the previous decade came together to create a practical modern bicycle. It began with the concept of two spoked wheels of equal size on a tubular frame followed by the invention of pneumatic tires to provide a smoother ride and propulsion from pedals connected to a chain driven sprocket.

However, early braking systems were less than adequate until the invention of the coaster brake in 1898. Wheels didn’t come cheap, ranging from $25 for a used bicycle in the mid-1890s to over $100 for the finest models in 1890s’ dollars, a luxury for most people at that time.