The track of broken dreams: Victoria Speedway filled with six years of thrills

Race fans may have come away from an evening at the Victoria Speedway dusty from the 35 or 40 stock cars churning up the clay track as they roared around the half-mile dirt oval, racing 25 to 50 laps, but, after cheering on some of the best drivers in the Northeast competing for the checkered flag, they had certainly gotten their fill of excitement and thrills for the price of their $2 admission.

Stock car racing originated in the South during the Prohibition years when stripped-down cars had been modified into exceedingly fast vehicles enabling bootleggers hauling illegal moonshine to evade the government revenue agents attempting to chase them down. Soon, when they weren’t busy running moonshine, these southerners were pitting their souped-up cars against one another in pastures or on country roads in informal competitions. By the mid-1930s, stock car racing as a race track sport had evolved in the South.

After World War II, the popularity of stock car racing took off, spreading to other parts of the country, and was especially appealing to working men and car enthusiasts. Fonda Speedway and Lebanon Valley Speedway were solidly established tracks in this area by the time the Victoria Speedway on Route 20 in Dunnsville opened in 1960.

At that time, a stock car was a stripped down American car, often a 1930s coupe, requiring that any modifications be made with parts available to the public at the typical auto dealer’s showroom.

With the increasing popularity of stock car racing and race tracks, it was obvious that standardization of rules and regulations was necessary, leading to the formation in 1948 of NASCAR, the National Association of Stock Car Racing, under the direction of Bill France and still owned by the France family.

NASCAR sanctioned race tracks and drivers, setting rules of operation for both racing and driving, and enforcing rules with fines or withdrawal of sanction.

Lou D’Amico, a Rotterdam garage owner and stock car enthusiast, had long dreamed of running his own race track. His opportunity came in 1960 when he signed a lease for the Victoria racetrack, no longer in use as a harness track.

Renaming it Victoria Speedway, the publicity release given out to area newspapers stated $35,000 had been invested in track improvements, including the best auto racing lights in this part of the country and a metal hub rail for the protection of both drivers and fans. The stands could seat 5,000 onlookers and, because the backstretch was elevated eight feet, every seat in the stands had a full view of the action.

Local volunteer firemen provided fire protection during races and handled parking. Both the Altamont and Fort Hunter departments were involved, although it’s not known if they participated all the years the speedway was running or if other departments were involved as well.

Victoria opened in August 1960, running into October. Races were scheduled for Friday nights as the long established Fonda Speedway had already claimed Saturday nights. Unfortunately, the first scheduled race was rained out, a bad omen as rainouts plagued the speedway during the years it operated.

The next two races fared better with 2,800 and 3,200 fans crowding the stands. Because NASCAR drivers were limited to racing only on NASCAR-sanctioned tracks, that first year many drivers raced under assumed names with their car numbers altered.

By opening day in 1961, promoter Lou D’Amico had obtained NASCAR sanction, allowing well known, popular NASCAR drivers to race there openly. Among those who raced and won at the Victoria Speedway were Pete Corey, Steve Danish, Lou Lazzaro, Howie Westervelt, Ken Shoemaker, “Jeep” Herbert, and Bill Wimble who had been named the 1960 National Co-Champion of his driving class.

All of these drivers are now honored in the New York State Stock Car Association’s Hall of Fame at the Saratoga Racing Museum and are still fondly remembered by stock car fans.

Newspaper articles did not give purse amounts but, in addition to winning money, NASCAR drivers were competing for points, which at that time were based on the purse size and the drivers’ finishing position in the race. NASCAR kept track of this and the number of points amassed got Bill Wimble his award.

Unforgettable moments

One tremendously emotional event early in that 1961 season was Pete Corey’s “brilliant” comeback race victory, returning to racing with a prosthesis after having suffered the loss of his left leg below the knee in a dreadful crash at Fonda Speedway the year before.

Imagine the fans’ excitement as he came from behind to win. By August, he was the leading driver at Victoria winning the 50-lap summer championship race that awarded him double NASCAR points. He was tremendously popular with the fans and it was said he was such a star that he got area sportswriters to pay more attention to stock car racing.

A never-to-be-forgotten moment at Victoria occurred that August when in the 14th lap of a 25-lap race, Ken Shoemaker’s engine blew, sending his car spinning into the path of Mel Austin’s car. After colliding with Shoemaker, Austin’s car went out of control, plowing through steel hub rails into the infield where it smashed into the announcer’s stand and shoved it eight feet off its footing.

Ambulances had to be called in to take the five people, including Ken Shoemaker, who were injured, to area hospitals. Worst off was John Miller, Altamont’s mayor whose leg was fractured in three places and his ankle dislocated, landing him in Albany Med for over a week.

He had attended the race that evening as one of the Altamont firemen on duty. After all that commotion, racing was called off for the night!

Across Route 20 from the Victoria Speedway was the Swiss Inn, a well known restaurant where a Victoria Speedway awards dinner took place in March 1962. High-point drivers’ awards were given out with Pete Corey taking first.

Present at the event was Bob Sall, NASCAR’s chief official in the Northeast who handed out the NASCAR Sportsman of the Year Trophy to Howie Westervelt, who had stopped his car during a race to rescue a fellow driver from a burning crash.

Regular press releases during the 1962 season appeared, giving details of upcoming races on the “lightning fast track” and the outcomes of the previous races, whetting the appetite of the race fans who often drove considerable distances to cheer on the outstanding drivers racing at Victoria.

Three 10-lap heats and a 10-lap consolation to determine starting positions and then a main feature of anywhere from 25 to 50 laps was the usual Friday-night schedule. The sound made by 35 or 40 cars at high speed created considerable noise that could be heard by residents quite a ways away. The track announcer was Bill Carpenter, a WGY radio and TV personality.

1962: “Fans on their feet”

Perfect weather, a big crowd, and drivers who put on “a tremendous show” kicked off the 1962 season. The turns had been widened by 20 feet, resulting in faster lap times while race-goers found new bleachers and concession stands with an improved public-address system.

Special events that year included a 50-lap race for Victoria’s summer championship and a 50-lap drivers’ benefit allowing them to split the ticket receipts.

If newspaper coverage wasn’t overly exaggerated that season, there was some real excitement at Victoria. The vivid sportswriting was loaded with phrases such as “full route four car battle,” “ barreled into the lead,” “a blazing four car battle,” “recovered from his spinout with a masterful bit of driving,” “blasted by Wimble,” “a nip and tuck three car battle,” or “a bumper battle.”

“In both features this season four or five cars have gone the entire distance bumper to bumper with the lead changing from one car to another,” said one account. “It kept fans on their feet through most of the features.”

The Victoria Speedway seemed in 1962 to have great success, but how the track fared in 1963 isn’t clear because there was no coverage in The Altamont Enterprise, though perhaps there was more in the Albany or Schenectady papers.

In February 1964, Lou D’Amico announced that the Victoria Speedway was again signed with NASCAR. In September, a 50-lap Tri-State Championship Race was to be run there with 35 drivers. Again, there was very little Altamont Enterprise coverage.

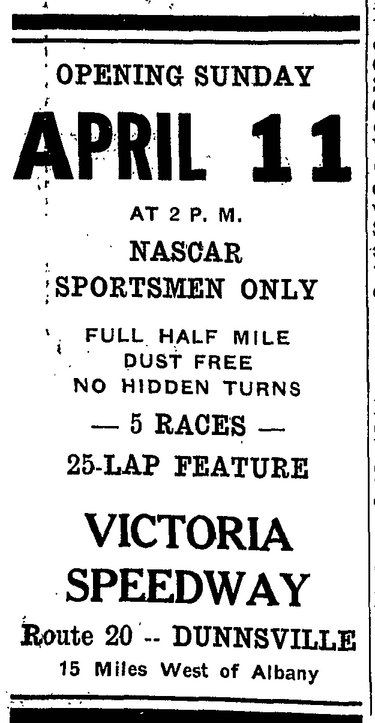

The 1965 opening of the Victoria Speedway was scheduled for Sunday afternoon, April 11, the earliest opening date it had attempted. President D’Amico reasoned that it gave “fans starved for a glimpse of their favorite sport through the long winter months, a chance to see stock car action without freezing in the process.”

It snowed, race canceled!

During cool weather, the races would be run on Sunday afternoon, then switching to Wednesday nights for the remainder of the season. With the opening of the new, well financed NASCAR Albany-Saratoga Speedway in Malta, Victoria lost its Friday night race time, and was forced to switch to racing on Wednesday nights.

Wednesday was a work night, the track facilities couldn’t compare to Fonda or the new track, and attendance began to decline.

New York State in 1965 suffered an extreme drought yet at Victoria nine out of 24 events ended up being canceled due to weather. In early July, a brief notice in the sports pages of The Schenectady Gazette observed that Victoria had been forced to cancel five out of the last six events.

Not only did cancellations have an effect on the gate, but the costs of preparing the dirt track ranged from between $300 and $500. Canceling as the result of a passing shower was a real loss.

Before the 30-lap main event began on May 6, D’Amico regretfully announced that, unless there was more support from fans, the track would be forced to close down as the cost of operation was increasing while attendance was decreasing.

An exciting race followed his plea with Kenny Shoemaker taking the race from Lou Lazzaro by half a lap. Somehow D’Amico found the funds to keep the track in operation that summer because racing continued.

During those years, NASCAR drivers raced at Lebanon Valley because of the attractive $1,000 purses that were divided up among those taking the first several places in a race. At first, to evade NASCAR regulations, they raced under assumed names, then drivers such as Bill Wimble and Pete Corey became bolder, racing under their actual names.

Drivers strike

After Lou Lazzaro, Ken Shoemaker, and Pete Corey openly won the first three places in a Lebanon race during May l965, NASCAR cracked down and assessed some stiff fines. Driver resentment was strong and they decided to take action by threatening to boycott local NASCAR tracks, beginning with the most vulnerable track, Victoria Speedway.

The management at Fonda, which had gotten wind of drivers’ intentions, knew what kind of effect a drivers’ strike would have on their track attendance Saturday night after a successful boycott at Victoria on Wednesday and knew they must head it off.

At Victoria on a July Wednesday evening, the drivers and their cars pulled in early but, instead of signing in at the track, they had gathered in the parking lot of the Swiss Inn across Route 20.

The Fonda management made a preemptive move by contacting NASCAR to get permission for race cars with larger engines, a different class of car from the type of stock cars that had been running at both of these speedways. Next they arranged through NASCAR to get 10 top modified drivers to bring their rigs up from Flemington, New Jersey to race at Victoria.

Knowing Lou D’Amico didn’t have the money to cover the cost of bringing in these drivers, the Fonda management secretly slipped him $1,000 to cover the expense. The Jersey drivers were told they were heading to upstate New York to help out a track with declining attendance.

When fans began arriving and found their favorite drivers boycotting the track, most refused to go in. Suddenly the pack of modified cars began rolling up Route 20 and entered the track.

Once the sound of revving engines could be heard, fans headed into the track, abandoning the strikers. But as soon as the Jersey drivers realized that the real reason they had been called to Victoria was to act as strikebreakers, they refused to race and insisted the other drivers’ fines be waived.

Eventually the races went on and after this modified cars with larger engines could race at the two tracks.

1966: Closed for good

By the time the track opened in 1966, it was no longer sanctioned by NASCAR and the publicity release announced that it would operate as an independent track open to any driver. Quoting Lou D’Amico, “We feel an independent program will give the fans better competition and larger fields.”

He claimed fans would continue to see the familiar big-time drivers who had been at the track previous years. He attempted to make an advantage of the Wednesday night meets by claiming that drivers could have any damage or trouble with their cars repaired and ready to go for their next race by Friday night.

The speedway just couldn’t make it with the competition from larger, nearby tracks, the work-night schedule and the cost of admission to more than one track by fans. Early in the summer of 1966, Victoria Speedway closed for good.

As a postscript to the Victoria story, a legal notice in The Altamont Enterprise on Nov. 3, 1972 announced a public hearing was scheduled Nov. 17, 1972 to review the case of Victoria Speedway. Ken Shoemaker and Lester Alberti were requesting an amendment to a special-use permit to make alterations allowing them to reopen the Victoria Speedway for racing.

They presented a petition with 400 signatures in favor of resumption of racing at the track. Their request was turned down and after the Guilderland Zoning Board of Appeals reconsidered it early in 1973; the application was again rejected with Board Chairman Paul Empie giving many reasons for denial based on the fact the plans were not in “accordance with regulations.”

Shoemaker in his autobiography claimed there were only five houses within a mile of the track, except that this was politics in a small town and “they were trying to show their power.”

The Victoria track might be called the track of broken dreams, both for Charles Russo’s harness track, followed a few years later by Lou D’Amico’s stock car speedway. And, to add insult to injury in “‘Car Coming’: An Auto Racing History of New York State,” probably the definitive history, the Victoria Speedway is listed as having been located in Duanesburg!